A paper for the IEEE “big humanities” workshop, written in collaboration with Michael L. Black, Loretta Auvil, and Boris Capitanu, is available on arXiv now as a preprint.

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers is an odd venue for literary history, and our paper ends up touching so many disciplinary bases that it may be distracting.* So I thought I’d pull out four issues of interest to humanists and discuss them briefly here; I’m also taking the occasion to add a little information about gender that we uncovered too late to include in the paper itself.

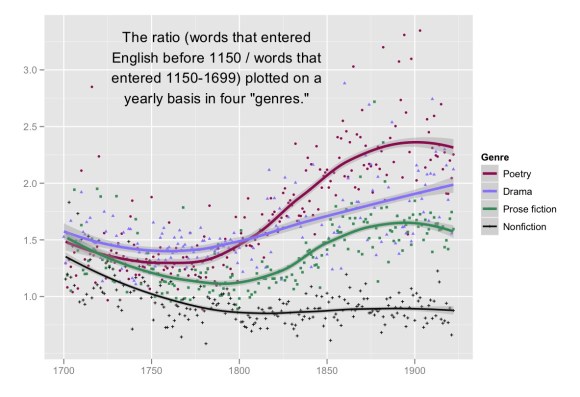

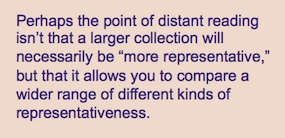

1) The overall point about genre. Our title, “Mapping Mutable Genres in Structurally Complex Volumes,” may sound like the sort of impossible task heroines are assigned in fairy tales. But the paper argues that the blurry mutability of genres is actually a strong argument for a digital approach to their history. If we could start from some consensus list of categories, it would be easy to crowdsource the history of genre: we’d each take a list of definitions and fan out through the archive. But centuries of debate haven’t yet produced stable definitions of genre. In that context, the advantage of algorithmic mapping is that it can be comprehensive and provisional at the same time. If you change your mind about underlying categories, you can just choose a different set of training examples and hit “run” again. In fact we may never need to reach a consensus about definitions in order to have an interesting conversation about the macroscopic history of genre.

2) A workset of 32,209 volumes of English-language fiction. On the other hand, certain broad categories aren’t going to be terribly controversial. We can probably agree about volumes — and eventually specific page ranges — that contain (for instance) prose fiction and nonfiction, narrative and lyric poetry, and drama in verse, or prose, or some mixture of the two. (Not to mention interesting genres like “publishers’ ads at the back of the volume.”) As a first pass at this problem, we extract a workset of 32,209 volumes containing prose fiction from a collection of 469,200 eighteenth- and nineteenth-century volumes in HathiTrust Digital Library. The metadata for this workset is publicly available from Illinois’ institutional repository. More substantial page-level worksets will soon be produced and archived at HathiTrust Research Center.

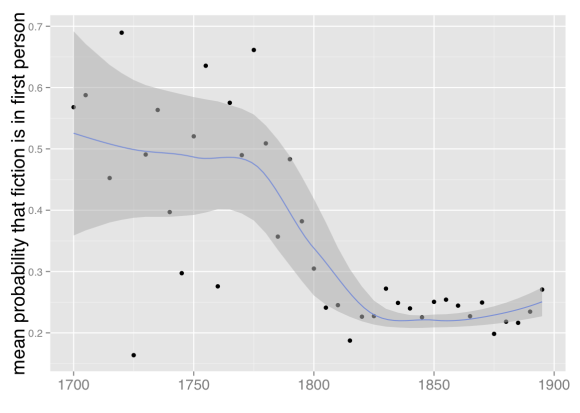

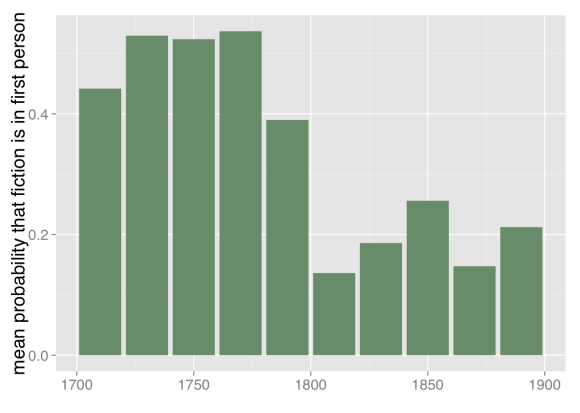

3) The declining prevalence of first-person narration. Once we’ve identified this fiction workset, we switch gears to consider point of view — frankly, because it’s a temptingly easy problem with clear literary significance. Though the fiction workset we’re using is defined more narrowly than it was last February, we confirm the result I glimpsed at that point, which is that the prevalence of first-person point of view declines significantly toward the end of the eighteenth century and then remains largely stable for the nineteenth.

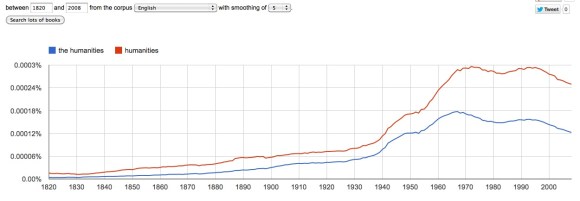

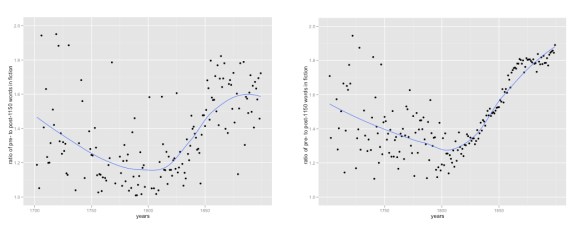

We can also confirm that result in a way I’m finding increasingly useful, which is to test it in a collection of a completely different sort. The HathiTrust collection includes reprints, which means that popular works have more weight in the collection than a novel printed only once. It also means that many volumes carry a date much later than their first date of publication. In some ways this gives a more accurate picture of print culture (an approximation to “what everyone read,” to borrow Scott Weingart’s phrase), but one could also argue for a different kind of representativeness, where each volume would be included only once, in a record dated to its first publication (an attempt to represent “what everyone wrote”).

Fortunately, Jordan Sellers and I produced a collection like that a few years ago, and we can run the same point-of-view classifier on this very different set of 774 fiction volumes (metadata available), selected by multiple hands from multiple sources (including TCP-ECCO, the Brown Women Writers Project, and the Internet Archive). Doing that reveals broadly the same trend line we saw in the HathiTrust collection. No collection can be absolutely representative (for one thing, because we don’t agree on what we ought to be representing). But discovering parallel results in collections that were constructed very differently does give me some confidence that we’re looking at a real trend.

4. Gender and point of view. In the process of classifying works of fiction, we stumbled on interesting thematic patterns associated with point of view. Features associated with first-person perspective include first-person pronouns, obviously, but also number words and words associated with sea travel. Some of this association may be explained by the surprising persistence of a particular two-century-long genre, the Robinsonade. A castaway premise obviously encourages first-person narration, but the colonial impulse in the Robinsonade also seems to have encouraged acquisitive enumeration of the objects (goats, barrels, guns, slaves) its European narrators find on ostensibly deserted islands. Thus all the number words. (But this association of first-person perspective with colonial settings and acquisitive enumeration may well extend beyond the boundaries of the Robinsonade to other genres of adventure fiction.)

Third-person perspective, on the other hand, is durably associated with words for domestic relationships (husband, lover, marriage). We’re still trying to understand these associations; they could be consequences of a preference for third-person perspective in, say, courtship fiction. But third-person pronouns correlate particularly strongly with words for feminine roles (girl, daughter, woman) — which suggests that there might also be a more specifically gendered dimension to this question.

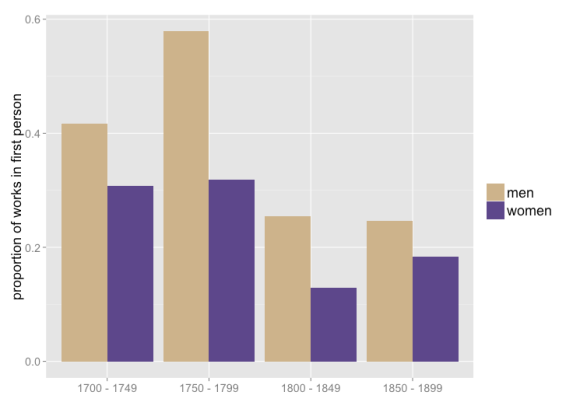

Since transmitting our paper to the IEEE I’ve had a chance to investigate this hypothesis in the smaller of the two collections we used for that paper — 774 works of fiction between 1700 and 1899: 521 by men, 249 by women, and four not characterized by gender. (Mike Black and Jordan Sellers recorded this gender data by hand.) In this collection, it does appear that male writers choose first-person perspective significantly more than women do. The gender gap persists across the whole timespan, although it might be fading toward the end of the nineteenth century.

Over the whole timespan, women use first person in roughly 23% of their works, and men use it in roughly 35% of their works.** That’s not a huge difference, but in relative terms it’s substantial. (Men are using first person 52% more than women). The Bayesian mafia have made me wary of p-values, but if you still care: a chi-squared test on the 2×2 contingency table of gender and point of view gives p < 0.001. (Attentive readers may already be wondering whether the decline of first person might be partly explained by an increase in the proportion of women writers. But actually, in this collection, works by women have a distribution that skews slightly earlier than that of works by men.)

These are very preliminary results. 774 volumes is a small set when you could test 32,209. At the recent HTRC Uncamp, Stacy Kowalczyk described a method for gender identification in the larger HathiTrust corpus, which we will be eager to borrow once it’s published. Also, the mere presence of an association between gender and point of view doesn’t answer any of the questions literary critics will really want to pose about this phenomenon — like, why is point of view associated with gender? Is this actually a direct consequence of gender, or is it an indirect consequence of some other variable like genre? Does this gendering of narrative perspective really fade toward the end of the nineteenth century? I don’t pretend to have answered any of those questions, all I’m doing here is flagging the existence of an interesting open question that will deserve further inquiry.

— — — — —

*Other papers for the panel are beginning to appear online. Here’s “Infectious Texts: Modeling Text Reuse in Nineteenth-Century Newspapers,” by David A. Smith, Ryan Cordell, and Elizabeth Maddock Dillon.

** We don’t actually represent point of view as a binary choice between first person or third person; the classifier reports probabilities as a continuous range between 0 and 1. But for purposes of this blog post I’ve simplified by dividing the works into two sets at the 0.5 mark. On this point, and for many other details of quantitative methodology, you’ll want to consult the paper itself.