by Ted Underwood and Jordan Sellers

Part of this project will appear next year — revised and improved — in MLQ. But we’ve decided to release it as a free-standing draft rather than a preprint, because it allows us to use color and to explore some puzzling leads that won’t fit into the physical limits of one journal article.

To understand the aesthetic standards that govern reception, we contrasted two samples of English-language poetry, drawn from different social contexts: 1) a group of 360 volumes that we chose by sampling reviews in prominent periodicals, 1820-1919, and 2) a group of 360 volumes sampled at random from HathiTrust Digital Library, many of them pretty obscure.

We were curious whether the difference in prestige between these books would be legible in the texts themselves. For instance, could you train a statistical model to predict whether a volume of poetry came from the “reviewed” or “random” sample just by looking at diction? And if you could, what social difference exactly would you be detecting?

Scholars sometimes suggest that high culture hadn’t differentiated from the rest of the literary field very sharply yet in the early 19th century [1: Huyssen 1986]. If so, books of poetry reviewed in prestigious contexts might be hard to identify in that part of the timeline. It might get easier toward the 20th century, as different poetic styles specialized to address (say) “high” and “middlebrow” audiences.

On the other hand, if writers became prominent by occupying the leading edge of a rapidly-moving wave, we might only be able to separate these samples by training a sequence of different models for different periods. For instance, prominent poets in the 1820s might be united by gloomy Byronism; in the 1850s they might share an interest in history; by the 1890s what they had in common might be the word “mauve.” As for the randomly-selected volumes, who knows? Maybe they would share only a tendency to trail thirty years behind the trend.

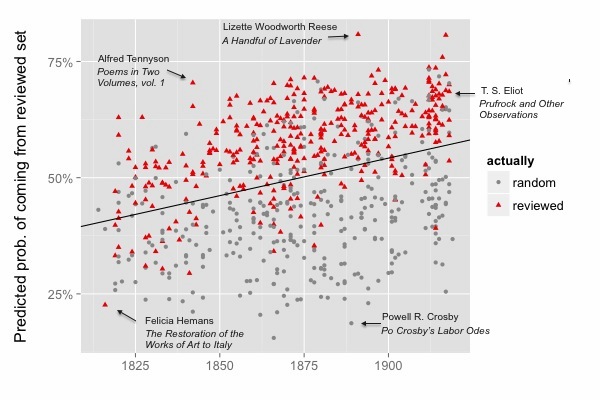

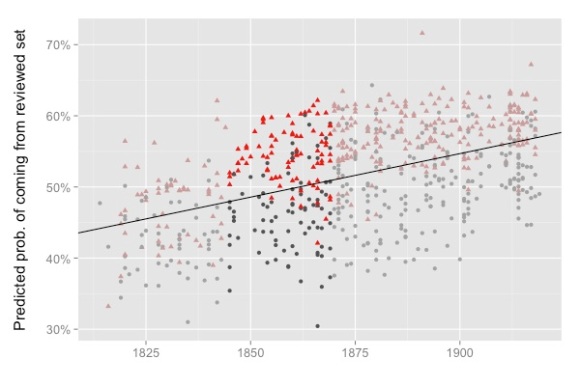

Since it seemed reasonable to assume that the standards governing reception had been volatile, we began by training a different model of poetic prestige for each twenty-year period. But we found, in practice, that the best way to separate these samples was to treat the whole period 1820-1919 as a single unit organized by a single set of aesthetic standards. You can click on the image that follows to see a slightly larger and clearer version.

In the image above, each point is a volume of poetry, colored according to its actual social provenance. The y axis expresses a statistical model’s prediction about that provenance: How likely is it that this volume came from the “reviewed” sample, based only on the words in the volume?

As you can see, the model does a pretty decent job of sorting the two samples. It’s not right all the time, because of course a volume’s reception is determined by a lot of factors other than language (politics, the whims of reviewers, social networks). But the model is right 79.2% of the time, which is often enough to suggest that volumes reviewed in prominent venues had something in common. The sort of poetic language that got reviewed is distinguished from other poetic traditions not just toward the twentieth century, as we had expected, but throughout this period.

What’s even more puzzling is this: reviewed writers seem to have had the same thing in common throughout this century. The model is using essentially the same list of prestigious and banal words to separate Lord Byron from more obscure poets around 1819, and Christina Rossetti from more obscure poets around 1866, and T. S. Eliot from more obscure writers around 1917. That’s starting to sound like an oddly durable set of preferences. And actually, it’s even more durable than the image above suggests. A model trained on a quarter-century of the evidence can predict the other 75 years almost as accurately as a model trained on the whole century.

So how is it even possible to characterize a whole century of poetic reception — based on fourteen different periodicals from both sides of the Atlantic — with a single set of aesthetic standards? Weren’t there supposed to be a couple of “poetic revolutions” in this century somewhere? W. B. Yeats certainly thought that one happened in the 1890s [2].

There’s another curious detail implied in the image above: why is the boundary between “reviewed” and “random” volumes drifting upward across the timeline? Technically, that’s an error. Volumes are not really “more likely to be reviewed” just because they were published later. But this is an error of an interesting kind. The model doesn’t know when these volumes were published: the dataset drifts upward because words that were more common in reviewed volumes across this period turn out to be more common in all volumes by the end of the period. If you divide the timeline into parts, the same pattern recurs in each part; and — to leak a detail from the next stage of this project — it also happens when we model fiction. That starts to suggest an interestingly general connection between synchronic judgment and diachronic change.

And there’s more. The detailed differences between reviewed and random poetry are interesting. In the article, we examine a haunting passage from Christina Rossetti; it turns out the model likes “haunting.” We also generalize about the theory of representativeness underpinning distant reading, and ask how our contemporary pedagogical canon looks when viewed by nineteenth-century aesthetic standards.

But all this, obviously, is too much to discuss in a blog post. See the article itself for our actual attempt to understand these puzzles.

We’ve released our code and data on Github, and hope readers will find flaws in our reasoning so we can improve the project. But this draft has been bounced off a couple of audiences already; at this point it’s stable enough to be cited and criticized. So, after some reflection, we’ve closed comments on this post in order to encourage a more public sort of critique. If we’re overlooking something, please say so in a blog post. It’s an explicit premise of the project that “being reviewed at all indicates a sort of literary distinction — even if the review is negative.”

[1]: One influential thesis holds that this division crystallized “in the last decades of the 19th century and the first few years of the 20th.” Andreas Huyssen, After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1986), viii.

[2]: W.B. Yeats dated the “revolt against Victorianism” and against “the poetical diction of everybody” to the 1890s. See discussion in Richard Fallis, “Yeats and the Reinterpretation of Victorian Poetry,” Victorian Poetry 14.2 (1976): 89-100.