While distant reading has taught us a lot about the history of fiction, it hasn’t done much yet to explain why we keep turning pages.

“Suspense” is the word we use to explain that impulse. But what is suspense? Does it require actual anxiety, or just uncertainty about what happens next? If suspense depends on not knowing what will happen, how can we enjoy re-reading familiar books? (Smuts 2009) And why do we enjoy being surprised? (Tobin 2018)

Beyond these big theoretical puzzles, there are historical questions scholars might like to ask about the way authors use chapter breaks to structure narrative revelation (Dames 2023, 219-38).

Right now, distant reading can’t fully answer any of these questions. When we want to measure surprise or novelty, for instance, we typically measure change in the verbal texture of a story from beginning to end. I made a coarse attempt of that kind in a blog post a few years ago. Other articles use better methods, and give us new ways to think about form (McGrath et al. 2018, Piper et al. 2023). But how closely does the pace of verbal change correlate with readers’ experience of uncertainty or surprise? We don’t know.

Autoregressive language models offer a tempting new angle on this problem, because they’re trained specifically to predict how a given text will continue. Intuitively, it feels like we could measure the predictability of a plot by first asking a model to continue the story, and then measuring the divergence between predicted continuation and real text. Even if this isn’t exactly how readers form expectations and experience surprise, it might begin to give us some leverage on the question.

Researchers have run a loosely similar experiment on very short stories contributed by experimental subjects (Sap et. al 2020). But scaling that up to published novels poses a challenge. For one thing, language models may not be equally good at imitating every style. A contemporary model’s failure to predict the next sentence by Jane Austen might just mean that it’s bad at channeling the Regency.

So, to factor style out of the question, let’s ask a model to predict what will happen in, say, the next three pages of a story — and then compare those predictions to its own summaries of the pages when it sees them.

Readers of a certain age will recognize this as a game Ernie invites Bert to play on “Sesame Street.”

To spell the method out more precisely: we move through a novel roughly 900 words at a time. On each pass, we give a language model both a recap of earlier events, and a new 900-word passage. We ask the model to summarize the new passage, and also ask it to predict what will happen next. Then we compare its prediction to the summary it generates when it actually sees the next passage, and measure cosine distance between the two sentence embeddings. A large distance means the model did a poor job of predicting “what would happen next.”

Does this have any relation to human uncertainty?

I’m not claiming that this is a good model of the way readers experience plot. We don’t have a good model of that yet! The more appropriate question to ask is: Does this correlate at all with anything human readers do?

We can check by asking a reader to do the same thing: read roughly 900-word passages and make predictions about the future. Then we can compare the human reader’s predictions to automatically-generated summaries.

When I did this for two novels that were complete blanks to me, my predictions tended to diverge from the actual course of the story in roughly the same places where the model found prediction difficult. So there does seem to be some relationship between a language model’s (in)ability to see what’s coming and a human reader’s.

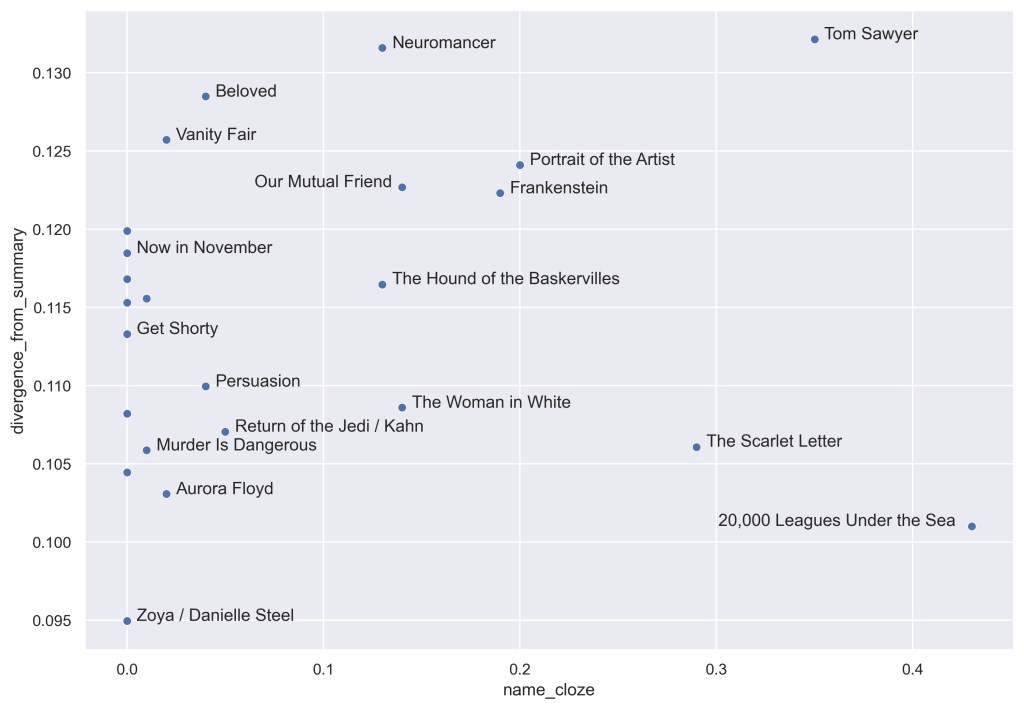

The image above also reveals that there are broad, consistent differences between books. For both people and models, some stories are easier to predict than others.

A reason not to trust this

Readers of this story may already anticipate the next twist—which is that of course we shouldn’t use LLMs to study uncertainty, because these models have already read many of the books we’re studying and will (presumably) already know the plot.

This is a particularly nasty problem because we don’t have a list of the books commercial models were trained on. We’re flying blind. But before we give up, let’s test how much of a problem this really poses. Researchers at Berkeley have defined a convenient test of the extent to which a model has memorized a book (Chang et al. 2023). In essence, they ask the model to fill in missing names.

Running this test, Chang et al. find that GPT-4 remembers many books in detail. Moreover, its ability to fill in masked names correlates with its accuracy on certain other tasks—like its ability to estimate date of publication. This could be a problem for questions about plot.

To avoid this problem (and also save money), I’ve been using GPT-3.5, which Chang et al. find is less prone to memorize books. But is that enough to address the problem? Let’s check. Below I’ve plotted the average divergence between prediction and summary for 25 novels on the y axis, and GPT-3.5’s ability to supply masked names in those texts on the x axis. If memorization was making prediction more accurate, we would expect to see a negative correlation: predictions’ divergence from summaries should go down as name_cloze accuracy goes up.

25 books is not enough for a conclusive answer, but so far I cannot measure any pattern of that kind. (If anything, there is a faint trend in the opposite direction.)

In an ideal world, researchers would use language models trained on open data sets that they know and control. But until we get to an ideal world, it looks like it may be possible to run proof-of-concept experiments with things like GPT-3.5, at least if we avoid extremely famous books.

Scrutinizing the image above, readers will probably notice that the most predictable book in this sample was Zoya, by Danielle Steel. Although Steel has a reputation that may encourage disparaging inferences — see Dan Sinykin, Big Fiction, for why — I don’t think we’re in a position to draw those inferences yet. The local rhythms that make prediction possible across three pages are not necessarily what critics mean when they use “predictable” to diss a book.

So what could we learn from predicting the next three pages?

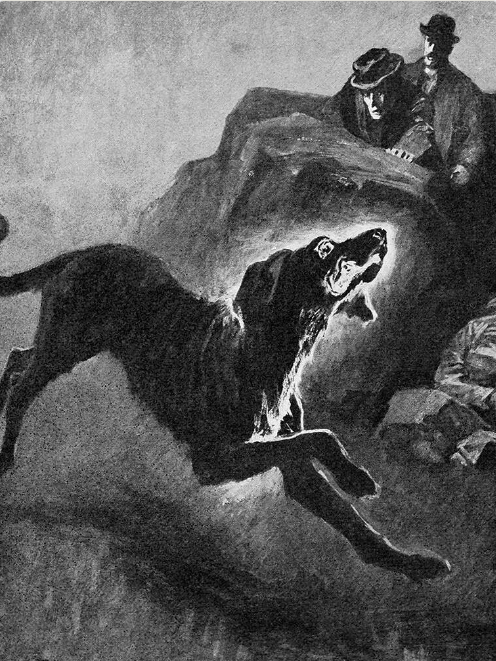

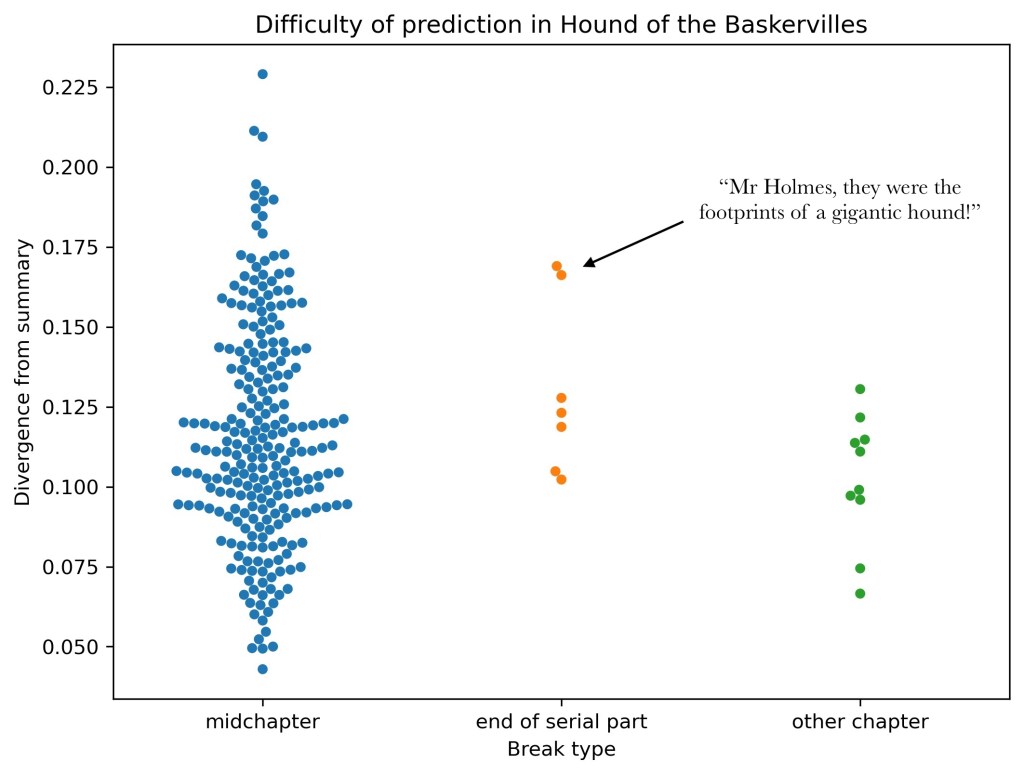

To consider one possible payoff: it might give us a handle on the way chapter-breaks, and other divides, structure the epistemic rhythms of fiction. For instance, many readers have noticed that the installments of novels originally published in magazines tend to end with an explicit mystery to ensure that you keep reading (Haugtvedt 2016 and Beekman 2017). In the first installment of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Hound of the Baskervilles (which covers two chapters), Watson and Holmes learn about a legendary curse that connects the family of the Baskervilles to a fiendish hound. In the final lines of the first installment, Holmes asks the family doctor about footprints found near the body of Sir Charles Baskerville. “A man’s or a woman’s?” Holmes asks. The doctor’s “voice sank almost to a whisper as he answered. ‘Mr Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!'” End installment.

Novels don’t have soundtracks. But unexplained, suggestive new information is as good as a sting: “Bum – bum – BUM!”

It appears that we can measure this cliffhanger effect: the serial installments of The Hound of the Baskervilles often end with a moment of heightened mystery — at least, if inability to predict the next three pages is any measure of mystery. When we measure predictive accuracy throughout the story, making four different passes to ensure we have roughly-900-word chunks aligned with all the chapter breaks, we find that predictions are farther from reality at the ends of serial installments. There is no similar effect at other chapter breaks.

Now, this is admittedly a cherry-picked example. So far, I have only looked at seven novels where we can distinguish the ends of serial installments from other kinds of chapter break (using data from Warhol et al). And I don’t see this pattern in all of them.

So I’m not yet making any historical argument about serialization and the rise of the cliffhanger. I’m just suggesting that it’s the kind of question someone could eventually address using this method. A doctoral student could do it, for instance, with a locally hosted model. (I don’t recommend doing it with GPT-3.5, because I dropped $150 or so on this post, and that might add up across a dissertation.) Some initial tests suggest to me that this approach will produce results significantly different than we’re getting with lexical methods.

Since I’m explicitly encouraging people to run with this, let me also say that someone actually writing a paper using this method might want to tinker with several things before trusting it:

- Measuring the distance between the embedding of one prediction sentence and one summary sentence is a crude way to measure expectation and surprise. Readers don’t necessarily form a single expectation about plot. Maybe it would be better to model expectation as a range of possibility?

- Related to this: models may need to be nudged to speculate and not just predict that current actions will continue.

- 900-word chunks may not be the only appropriate scale of analysis. When readers talk about narrative surprise they’re often thinking about larger arcs like “who will he marry?” or “who turns out to be the murderer?”

- We need a way to handle braided narratives where each chapter is devoted to a different group of characters (Garrett 1980). In a multi-plot story, the B or C plot will often not continue across a chapter break.

But we’re in a multi-plot narrative ourselves, so those problems may be solved by a different group of characters. This was just a blog post to share an idea and get people arguing about it. Tune in next time, for our thrilling conclusion. (Bum – bum – BUM!)

Code and data used for this post are available on Github.

The ideas discussed here were previously presented in Paris at a workshop on AI for the analysis of literary corpora, and in Copenhagen in a conference on generative methods in the social sciences and humanities. I’d like to thank the organizers of those events, esp. Thierry Poibeau, Anders Munk, and Rolf Lund, for stimulating conversation — and also many people in attendance, especially David Bamman, Lynn Cherny, and Meredith Martin. In writing code to query the OpenAI API, I borrowed snippets from Quinn Dombrowski (and also of course from GPT-4 itself oh brave new world &c). My thinking about 19c serialization was advanced by conversation with David Bishop and Eleanor Courtemanche, and by suggestions from Ryan Cordell and Elizabeth Foxwell on Bluesky.

References

Beekman, G. (2017) “Emotional Density, Suspense, and the Serialization of The Woman in White in All theYear Round.” Victorian Periodicals Review 50.1.

Chang, K., Cramer, M., Soni, S., & Bamman, D. (2023) “Speak, Memory: An Archaeology of Books known to ChatGPT / GPT-4,” https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.00118.

Dames, N. (2023) The Chapter: A Segmented History from Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press.

Garrett, P. (1980) The Victorian Multiplot Novel: Studies in Dialogical Form. Yale University Press.

Haugtvedt, E. (2016) “The Sympathy of Suspense: Gaskell and Braddon’s Slow and Fast Sensation Fiction in Family Magazines.” Victorian Periodicals Review 49.1.

McGrath, L., Higgins, D., & Hintze, A. (2018) “Measuring Modernist Novelty.” Journal of Cultural Analytics. https://culturalanalytics.org/article/11030-measuring-modernist-novelty

Piper, A., Xu, H., & Kolaczyk, E. D. (2023) “Modeling Narrative Revelation.” Computational Humanities Research 2023. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3558/paper6166.pdf

Sap, M., Horvitz, E., Choi, Y., Smith, N. A., & Pennebaker, J. (2020) “Recollection Versus Imagination: Exploring Human Memory and Cognition via Neural Language Models.” Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the ACL. https://aclanthology.org/2020.acl-main.178/

Sinykin, Dan. Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature. Columbia University Press, 2023.

Smuts, A. (2009) “The Paradox of Suspense.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/paradox-suspense/#SusSur

Tobin, V. (2018) The Elements of Surprise: Our Mental Limits and the Satisfactions of Plot. Harvard University Press.

Warhol, Robyn, et al., “Reading Like a Victorian,” https://readinglikeavictorian.osu.edu/.