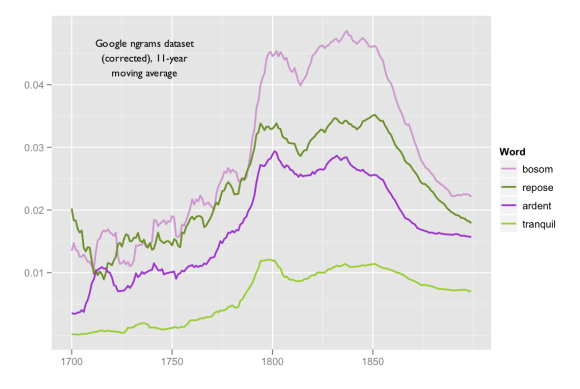

In my last post, I suggested that literary and nonliterary diction seem to have substantially diverged over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The vocabulary of fiction, for instance, becomes less like nonfiction prose at the same time as it becomes more like poetry.

It’s impossible to interpret a comparative result like this purely as evidence about one side of the comparison. We’re looking at a process of differentiation that involves changes on both sides: the language of nonfiction and fiction, for instance, may both have specialized in different ways.

This post is partly a response to very helpful suggestions I received from commenters, both on this blog and at Language Log. It’s especially a response to Ben Schmidt’s effort to reproduce my results using the Bookworm dataset. I also try two new measures of similarity toward the end of the post (cosine similarity and etymology) which I think interestingly sharpen the original hypothesis.

I have improved my number-crunching in four main ways (you can skip these if you’re bored):

1) In order to normalize corpus size across time, I’m now comparing equal-sized samples. Because the sample sizes are small relative to the larger collection, I have been repeating the sampling process five times and averaging results with a Fisher’s r-to-z transform. Repeated sampling doesn’t make a huge difference, but it slightly reduces noise.

2) My original blog post used 39-year slices of time that overlapped with each other, producing a smoothing effect. Ben Schmidt persuasively suggests that it would be better to use non-overlapping samples, so in this post I’m using non-overlapping 20-year slices of time.

3) I’m now running comparisons on the top 5,000 words in each pair of samples, rather than the top 5,000 words in the collection as a whole. This is a crucial and substantive change.

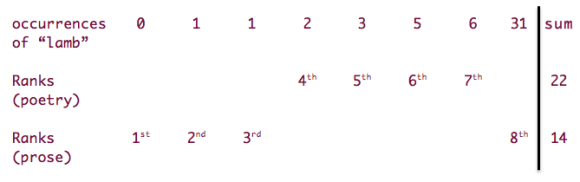

4) Instead of plotting a genre’s similarity to itself as a flat line of perfect similarity at the top of each plot, I plot self-similarity between two non-overlapping samples selected randomly from that genre. (Nick Lamb at Language Log recommended this approach.) This allows us to measure the internal homogeneity of a genre and use it as a control for the differentiation between genres.

Briefly, I think the central claims I was making in my original post hold up. But the constraints imposed by this newly-rigorous methodology have forced me to focus on nonfiction, fiction, and poetry. Our collections of biography and drama simply aren’t large enough yet to support equal-sized random samples across the whole period.

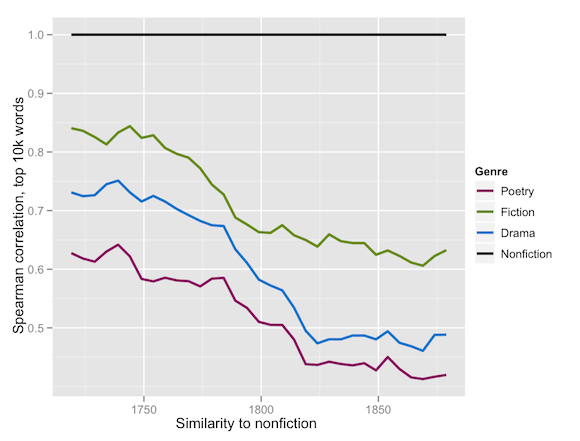

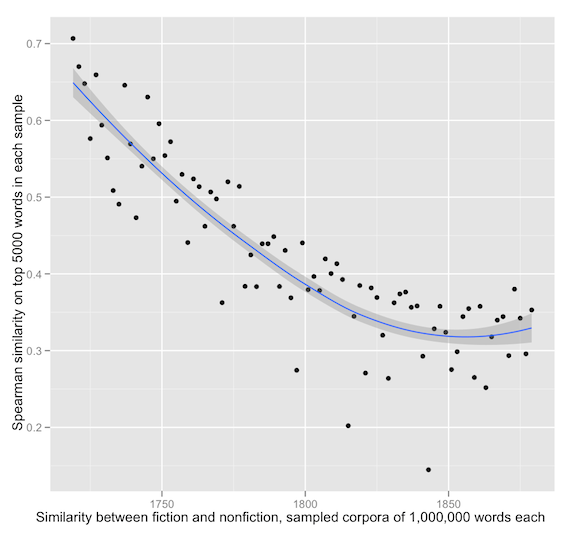

Here are the results for fiction compared to nonfiction, and nonfiction compared to itself.

This strongly supports the conclusion that fiction was becoming less like nonfiction, but also reveals that the internal homogeneity of the nonfiction corpus was decreasing, especially in the 18c. So some of the differentiation between fiction and nonfiction may be due to the internal diversification of nonfiction prose.

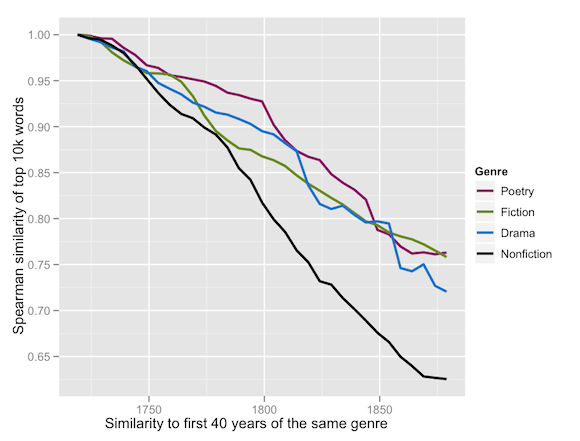

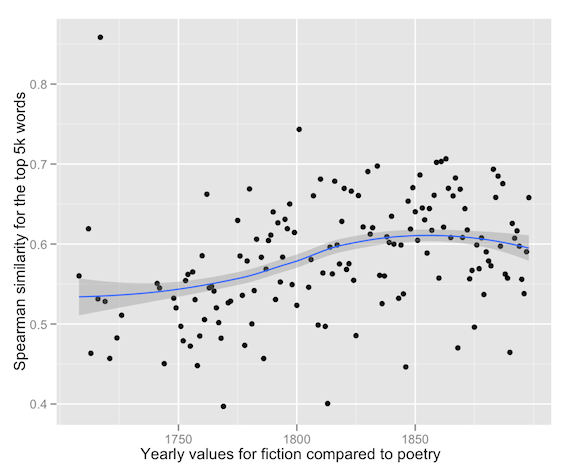

By contrast, here are the results for poetry compared to fiction, and fiction compared to itself.

Poetry and fiction are becoming more similar in the period 1720-1900. I should note that I’ve dropped the first datapoint, for the period 1700-1719, because it seemed to be an outlier. Also, we’re using a smaller sample size here, because my poetry collection won’t support 1 million word samples across the whole period. (We have stripped the prose introduction and notes from volumes of poetry, so they’re small.)

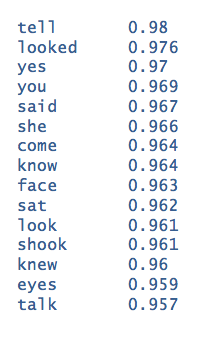

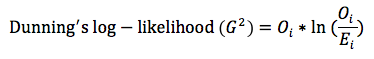

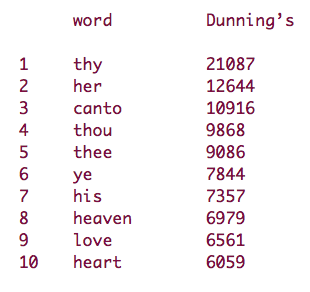

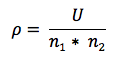

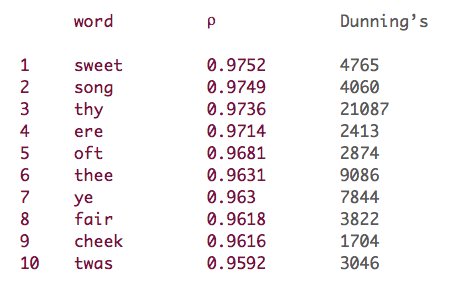

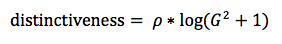

Another question that was raised, both by Ben and by Mark Liberman at Language Log, involved the relationship between “diction” and “topical content.” The Spearman correlation coefficient gives common and uncommon words equal weight, which means (in effect) that it makes no effort to distinguish style from content.

But there are other ways of contrasting diction. And I thought I might try them, because I wanted to figure out how much of the growing distance between fiction and nonfiction was due simply to the topical differentiation of nonfiction in this period. So in the next graph, I’m comparing the cosine similarity of million-word samples selected from fiction and nonfiction to distinct samples selected from nonfiction. Cosine similarity is a measure that, in effect, gives more weight to common words.

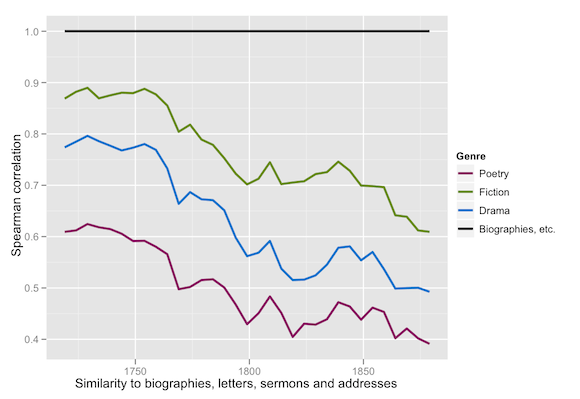

I was surprised by this result. When I get very stable numbers for any variable I usually assume that something is broken. But I ran this twice, and used the same code to make different comparisons, and the upshot is that samples of nonfiction really are very similar to other samples of nonfiction in the same period (as measured by cosine similarity). I assume this is because the growing topical heterogeneity that becomes visible in Spearman’s correlation makes less difference to a measure that focuses on common words. Fiction is much more diverse internally by this measure — which makes sense, frankly, because the most common words can be totally different in first-person and third-person fiction. But — to return to the theme of this post — the key thing is that there’s a dramatic differentiation of fiction and nonfiction in this period. Here, by contrast, are the results for nonfiction and poetry compared to fiction, as well as fiction compared to itself.

This graph is a little wriggly, and the underlying data points are pretty bouncy — because fiction is internally diverse when measured by cosine similarity, and it makes a rather bouncy reference point. But through all of that I think one key fact does emerge: by this measure, fiction looks more similar to nonfiction prose in the eighteenth century, and more similar to poetry in the nineteenth.

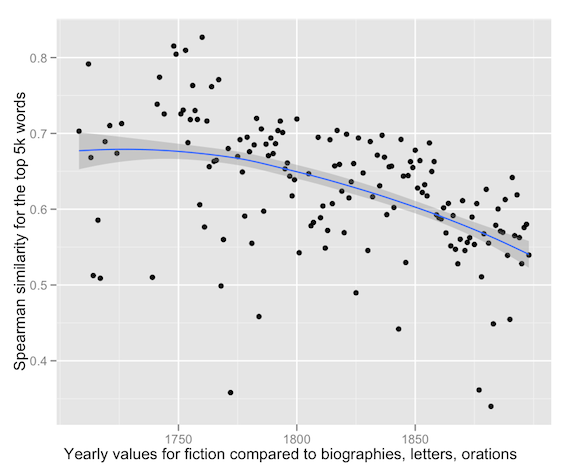

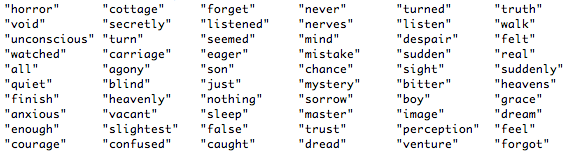

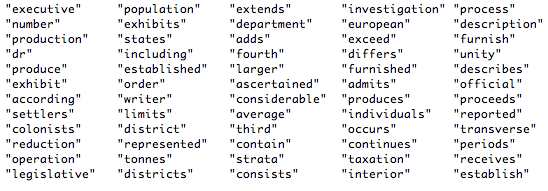

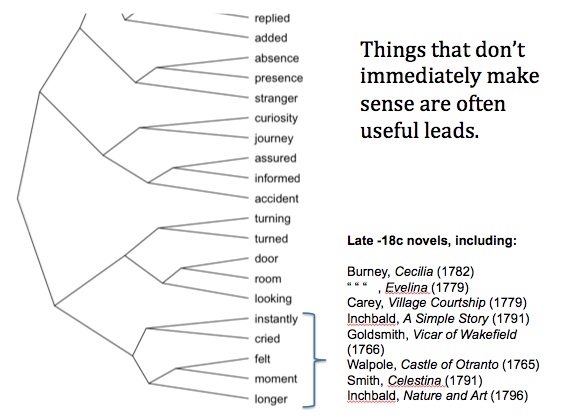

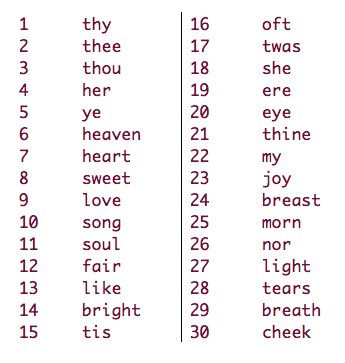

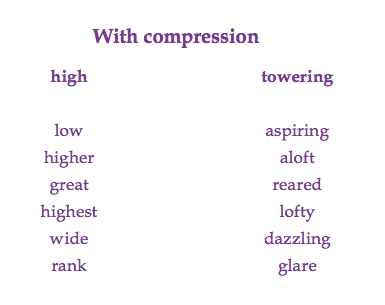

There’s a lot more to investigate here. In my original post I tried to identify some of the words that became more common in fiction as it became less like nonfiction. I’d like to run that again, in order to explain why fiction and poetry became more similar to each other. But I’ll save that for another day. I do want to offer one specific metric that might help us explain the differentiation of “literary” and “nonliterary” diction: the changing etymological character of the vocabulary in these genres.

Measuring the ratio of “pre-1150” to “post-1150” words is roughly like measuring the ratio of “Germanic” to “Latinate” diction, except that there are a number of pre-1150 words (like “school” and “wall”) that are technically “Latinate.” So this is essentially a way of measuring the relative “familiarity” or “informality” of a genre (Bar-Ilan and Berman 2007). (This graph is based on the top 10k words in the whole collection. I have excluded proper nouns, words that entered the language after 1699, and stopwords — determiners, pronouns, conjunctions, and prepositions.)

I think this graph may help explain why we have the impression that literary language became less specialized in this period. It may indeed have become more informal — perhaps even closer to the spoken language. But in doing so it became more distinct from other kinds of writing.

I’d like to thank everyone who responded to the original post: I got a lot of good ideas for collection development as well as new ways of slicing the collection. Katherine Harris, for instance, has convinced me to add more women writers to the collection; I’m hoping that I can get texts from the Brown Women Writers Project. This may also be a good moment to reiterate that the nineteenth-century part of the collection I’m working with was selected by Jordan Sellers, and these results should be understood as built on his research. Finally, I have put the R code that I used for most of these plots in my Open Data page, but it’s ugly and not commented yet; prettier code will appear later this weekend.

References

Laly Bar-Ilan and Ruth A. Berman, “Developing register differentiation: the Latinate-Germanic divide in English,” Linguistics 45 (2007): 1-35.