If the Internet is good for anything, it’s good for speeding up the Ent-like conversation between articles, to make that rumble more perceptible by human ears. I thought I might help the process along by summarizing the Stanford Literary Lab’s latest pamphlet — a single-authored piece by Franco Moretti, “‘Operationalizing’: or the function of measurement in modern literary theory.”

One of the many strengths of Moretti’s writing is a willingness to dramatize his own learning process. This pamphlet situates itself as a twist in the ongoing evolution of “computational criticism,” a turn from literary history to literary theory.

Measurement as a challenge to literary theory, one could say, echoing a famous essay by Hans Robert Jauss. This is not what I expected from the encounter of computation and criticism; I assumed, like so many others, that the new approach would change the history, rather than the theory of literature ….

Measurement challenges literary theory because it asks us to “operationalize” existing critical concepts — to say, for instance, exactly how we know that one character occupies more “space” in a work than another. Are we talking simply about the number of words they speak? or perhaps about their degree of interaction with other characters?

Moretti uses Alex Woloch’s concept of “character-space” as a specific example of what it means to operationalize a concept, but he’s more interested in exploring the broader epistemological question of what we gain by operationalizing things. When literary scholars discuss quantification, we often tacitly assume that measurement itself is on trial. We ask ourselves whether measurement is an adequate proxy for our existing critical concepts. Can mere numbers capture the ineffable nuances we assume they possess? Here, Moretti flips that assumption and suggests that measurement may have something to teach us about our concepts — as we’re forced to make them concrete, we may discover that we understood them imperfectly. At the end of the article, he suggests for instance (after begging divine forgiveness) that Hegel may have been wrong about “tragic collision.”

I think Moretti is frankly right about the broad question this pamphlet opens. If we engage quantitative methods seriously, they’re not going to remain confined to empirical observations about the history of predefined critical concepts. Quantification is going to push back against the concepts themselves, and spill over into theoretical debate. I warned y’all back in August that literary theory was “about to get interesting again,” and this is very much what I had in mind.

At this point in a scholarly review, the standard procedure is to point out that a work nevertheless possesses “oversights.” (Insight, meet blindness!) But I don’t think Moretti is actually blind to any of the reflections I add below. We have differences of rhetorical emphasis, which is not the same thing.

For instance, Moretti does acknowledge that trying to operationalize concepts could cause them to dissolve in our hands, if they’re revealed as unstable or badly framed (see his response to Bridgman on pp. 9-10). But he chooses to focus on a case where this doesn’t happen. Hegel’s concept of “tragic collision” holds together, on his account; we just learn something new about it.

In most of the quantitative projects I’m pursuing, this has not been my experience. For instance, in developing statistical models of genre, the first thing I learned was that critics use the word genre to cover a range of different kinds of categories, with different degrees of coherence and historical volatility. Instead of coming up with a single way to operationalize genre, I’m going to end up producing several different mapping strategies that address patterns on different scales.

Something similar might be true even about a concept like “character.” In Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale, for instance, characters are reduced to plot functions. Characters don’t have to be people or have agency: when the hero plucks a magic apple from a tree, the tree itself occupies the role of “donor.” On Propp’s account, it would be meaningless to represent a tale like “Le Petit Chaperon Rouge” as a social network. Our desire to imagine narrative as a network of interactions between imagined “people” (wolf ⇌ grandmother) presupposes a separation between nodes and edges that makes no sense for Propp. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that Moretti is wrong to represent Hamlet as a social network: Hamlet is not Red Riding Hood, and tragic drama arguably envisions character in a different way. In short, one of the things we might learn by operationalizing the term “character” is that the term has genuinely different meanings in different genres, obscured for us by the mere continuity of a verbal sign. [I should probably be citing Tzvetan Todorov here, The Poetics of Prose, chapter 5.]

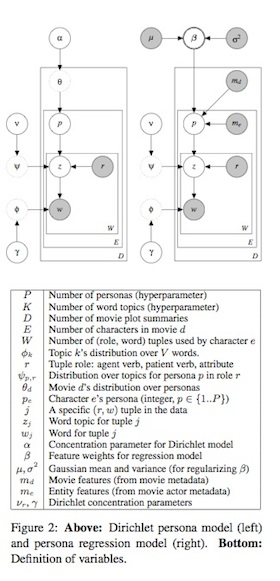

The illustration on the right is a probabilistic graphical model drawn from a paper on the “Latent Personas of Film Characters” by Bamman, O’Connor, and Smith. The model represents a network of conditional relationships between variables. Some of those variables can be observed (like words in a plot summary w and external information about the film being summarized md), but some have to be inferred, like recurring character types (p) that are hypothesized to structure film narrative.

Having empirically observed the effects of illustrations like this on literary scholars, I can report that they produce deep, Lovecraftian horror. Nothing looks bristlier and more positivist than plate notation.

But I think this is a tragic miscommunication produced by language barriers that both sides need to overcome. The point of model-building is actually to address the reservations and nuances that humanists correctly want to interject whenever the concept of “measurement” comes up. Many concepts can’t be directly measured. In fact, many of our critical concepts are only provisional hypotheses about unseen categories that might (or might not) structure literary discourse. Before we can attempt to operationalize those categories, we need to make underlying assumptions explicit. That’s precisely what a model allows us to do.

It’s probably going to turn out that many things are simply beyond our power to model: ideology and social change, for instance, are very important and not at all easy to model quantitatively. But I think Moretti is absolutely right that literary scholars have a lot to gain by trying to operationalize basic concepts like genre and character. In some cases we may be able to do that by direct measurement; in other cases it may require model-building. In some cases we may come away from the enterprise with a better definition of existing concepts; in other cases those concepts may dissolve in our hands, revealed as more unstable than even poststructuralists imagined. The only thing I would say confidently about this project is that it promises to be interesting.