When you stumble on an interesting problem, the question arises: do you blog the problem itself — or wait until you have a full solution to publish as an article?

In this case, I think the problem is too big to be solved by a single person anyway, so I might as well get it out there where we can all chip away at it. At the end of this post, I include a link to a page where you can also download the data and code I’m using.

When we compare groups of texts, we’re often interested in characterizing the contrast between them. But instead of characterizing the contrast, you could also just measure the distance between categories. For instance, you could generate a list of word frequencies for two genres, and then run a Spearman’s correlation test, to measure the rank-order similarity of their diction.

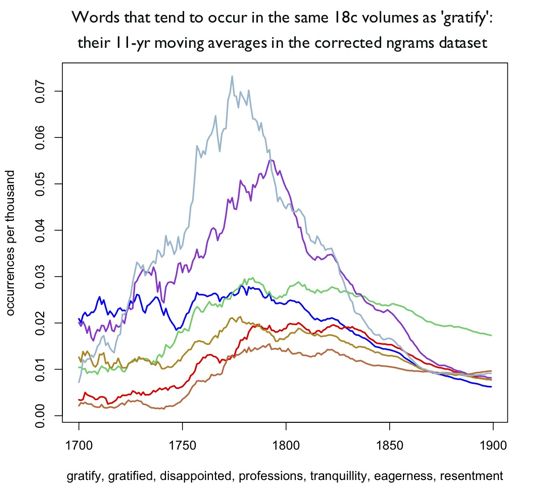

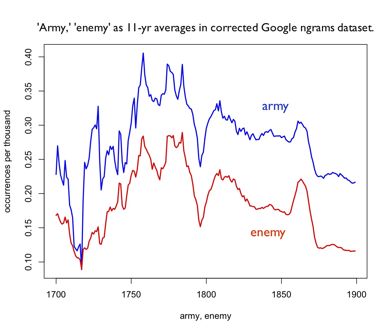

In isolation, a measure of similarity between two genres is hard to interpret. But if you run the test repeatedly to compare genres at different points in time, the changes can tell you when the diction of the genres becomes more or less similar.

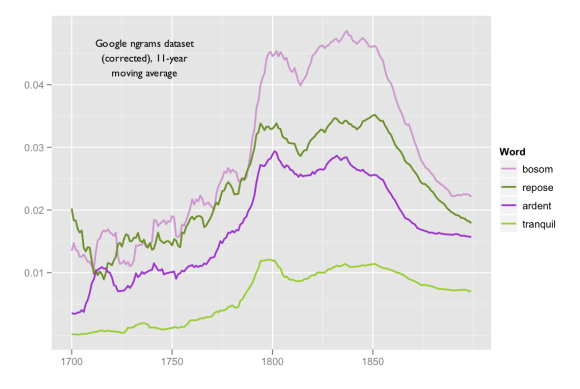

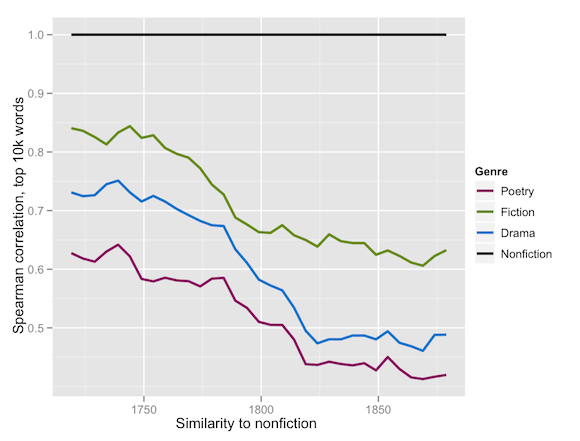

In the graph above, I’ve done that with four genres, in a collection of 3,724 eighteenth- and nineteenth-century volumes (constructed in part by TCP and in part by Jordan Sellers — see acknowledgments), using the 10,000 most frequent words in the collection, excluding proper nouns. The black line at the top is flat, because nonfiction is always similar to itself. But the other lines decline as poetry, drama, and fiction become progressively less similar to nonfiction where word choice is concerned. Unsurprisingly, prose fiction is always more similar to nonfiction than poetry is. But the steady decline in the similarity of all three genres to nonfiction is interesting. Literary histories of this period have tended to pivot on William Wordsworth’s rebellion against a specialized “poetic diction” — a story that would seem to suggest that the diction of 19c poetry should be less different from prose than 18c poetry had been. But that’s not the pattern we’re seeing here: instead it appears that a differentiation was setting in between literary and nonliterary language.

This should be described as a differentiation of “diction” rather than style. To separate style from content (for instance to determine authorship) you need to focus on the frequencies of common words. But when critics discuss “diction,” they’re equally interested, I think, in common and less common words — and that’s the kind of measure of similarity that Spearman’s correlation will give you (Kilgarriff 2001).

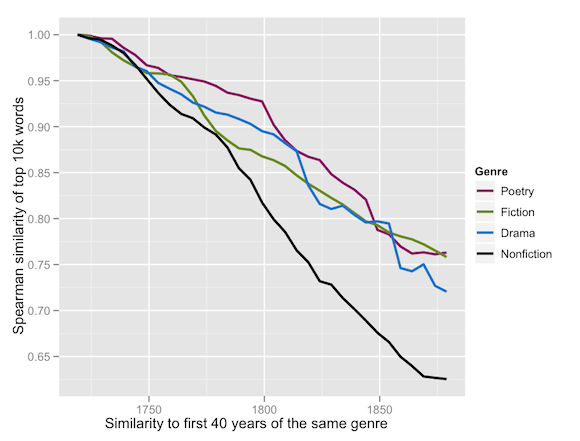

The graph above makes it look as though nonfiction was remaining constant while other genres drifted away from it. But we are after all graphing a comparison with two sides. This raises the question: were poetry, fiction, and drama changing relative to nonfiction, or was nonfiction changing relative to them? But of course the answer is “both.”

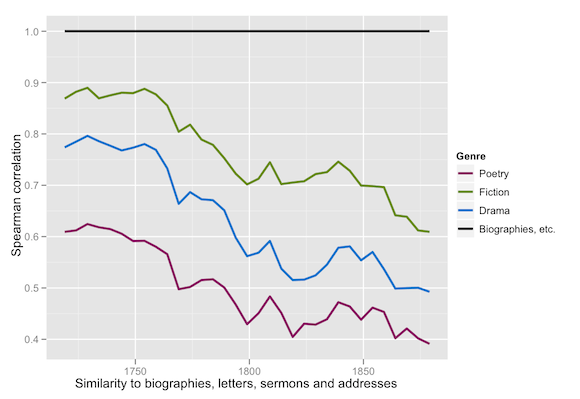

Here we’re comparing each genre to its own past. The language of nonfiction changes somewhat more rapidly than the language of the other genres, but none of them remain constant. There is no fixed reference point in this world, which is why I’m talking about the “differentiation” of two categories. But even granting that, we might want to pose another skeptical question: when literary genres become less like nonfiction, is that merely a sign of some instability in the definition of “nonfiction”? Did it happen mostly because, say, the nineteenth century started to publish on specialized scientific topics? We can address this question to some extent by selecting a more tightly defined subset of nonfiction as a reference point — say, biographies, letters, and orations.

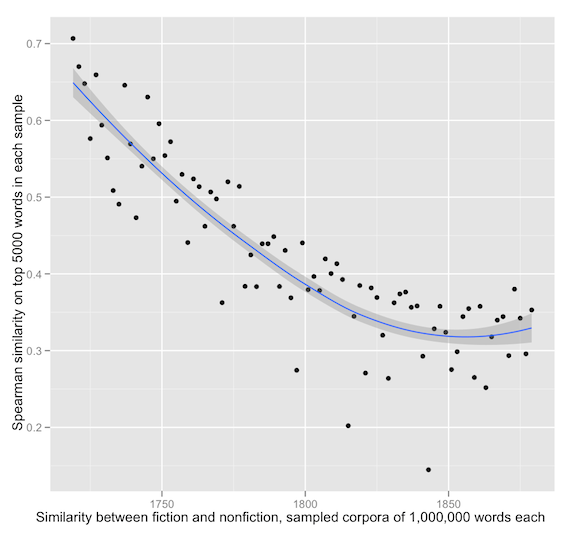

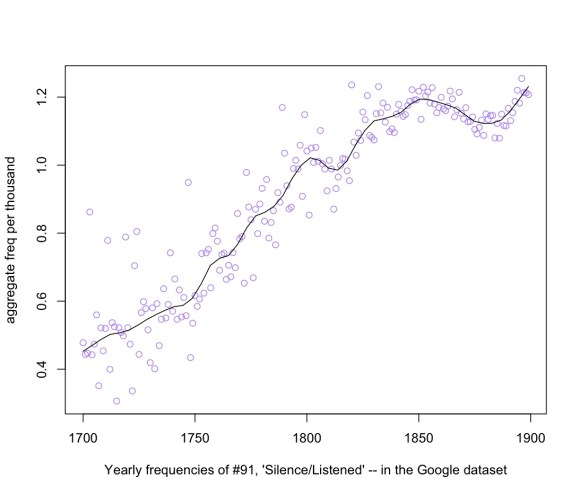

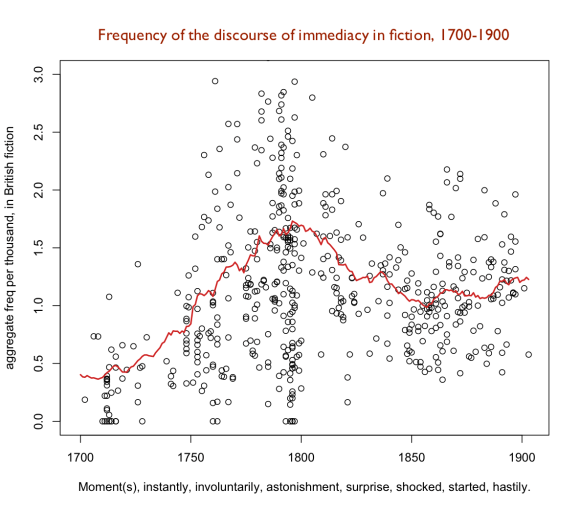

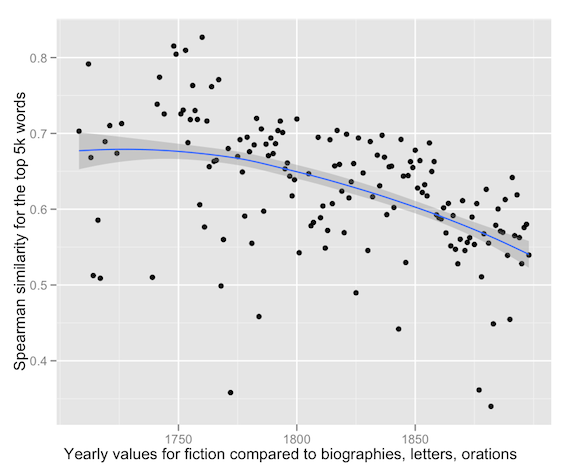

Even when we focus on this relatively stable category, we see significant differentiation. Two final skeptical questions need addressing before I try to explain what happened. First, I’ve been graphing results so far as solid lines, because our eyes can’t sort out individual data points for four different variables at once. But a numerically savvy reader will want to see some distributions and error bars before assessing the significance of these results. So here are yearly values for fiction. In some cases these are individual works of fiction, though when there are two or more works of fiction in a single year they have been summed and treated as a group. Each year of fiction is being compared against biographies, letters, and orations for 19 years on either side.

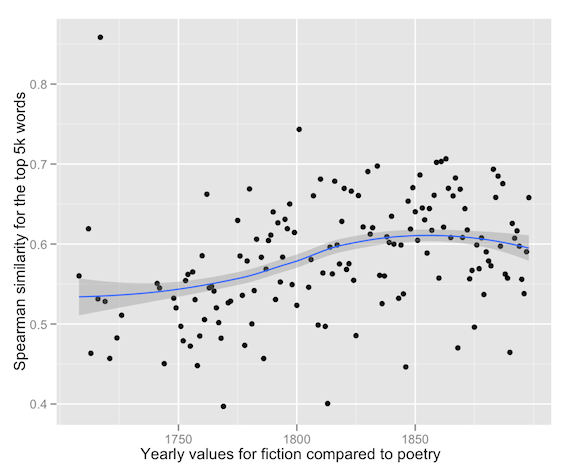

That’s a fairly persuasive trend. You may, however, notice that the Spearman similarities for individual years on this graph are about .1 lower than they were when we graphed fiction as a 39-year moving window. In principle Spearman similarity is independent of corpus size, but it can be affected by the diversity of a corpus. The similarity between two individual texts is generally going to be lower than the similarity between two large and diverse corpora. So could the changes we’ve seen be produced by changes in corpus size? There could be some effect, but I don’t think it’s large enough to explain the phenomenon. [See update at the bottom of this post. The results are in fact even clearer when you keep corpus size constant. -Ed.] The sizes of the corpora for different genres don’t change in a way that would produce the observed decreases in similarity; the fiction corpus, in particular, gets larger as it gets less like nonfiction. Meanwhile, it is at the same time becoming more like poetry. We’re dealing with some factor beyond corpus size.

So how then do we explain the differentiation of literary and nonliterary diction? As I started by saying, I don’t expect to provide a complete answer: I’m raising a question. But I can offer a few initial leads. In some ways it’s not surprising that novels would gradually become less like biographies and letters. The novel began very much as faked biography and faked correspondence. Over the course of the period 1700-1900 the novel developed a sharper generic identity, and one might expect it to develop a distinct diction. But the fact that poetry and drama seem to have experienced a similar shift (together with the fact that literary genres don’t seem to have diverged significantly from each other) begins to suggest that we’re looking at the emergence of a distinctively “literary” diction in this period.

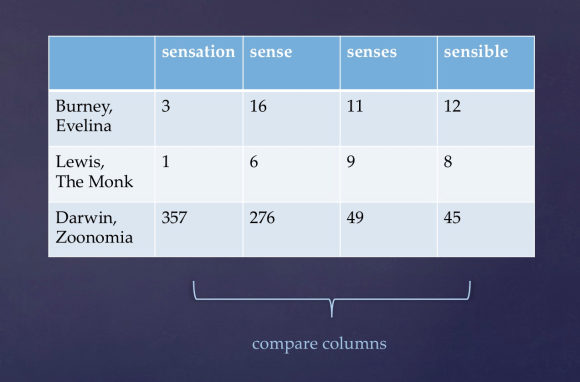

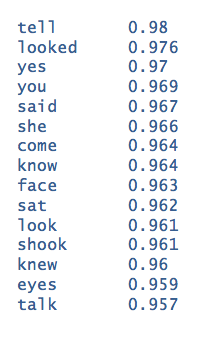

To investigate the character of that diction, we need to compare the vocabulary of genres at many different points. If we just compared late-nineteenth-century fiction to late-nineteenth-century nonfiction, we would get the vocabulary that characterized fiction at that moment, but we wouldn’t know which aspects of it were really new. I’ve done that on the side here, using the Mann-Whitney rho test I described in an earlier post. As you’ll see, the words that distinguish fiction from nonfiction from 1850 to 1900 are essentially a list of pronouns and verbs used to describe personal interaction. But that is true to some extent about fiction in any period. We want to know what aspects of diction had changed.

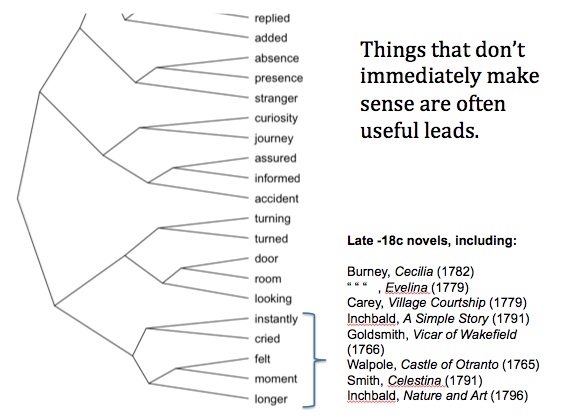

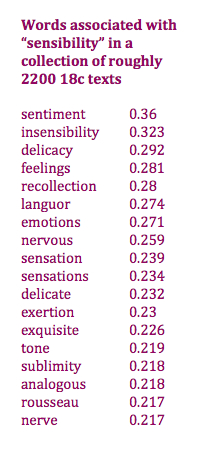

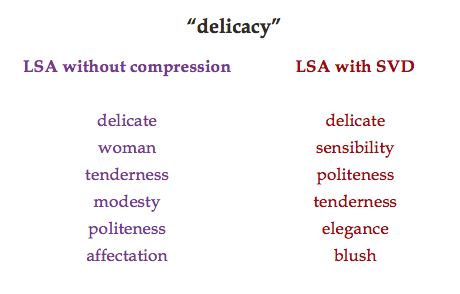

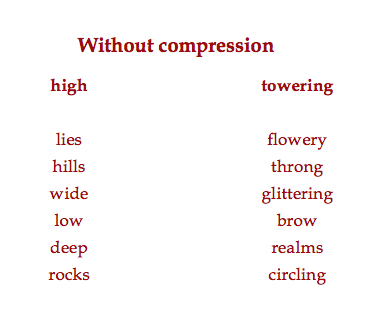

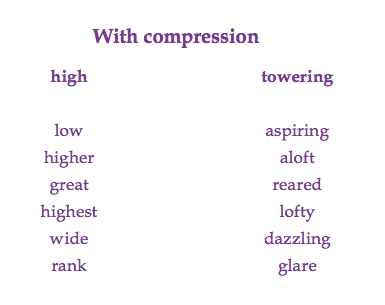

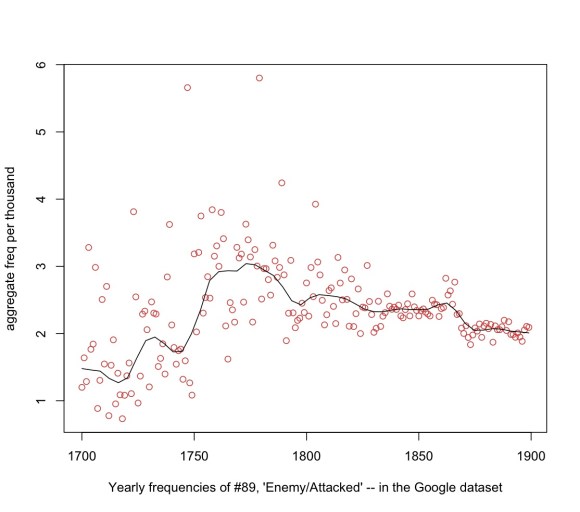

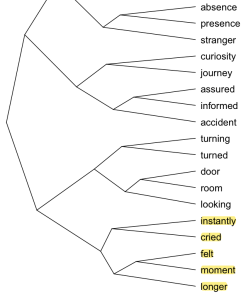

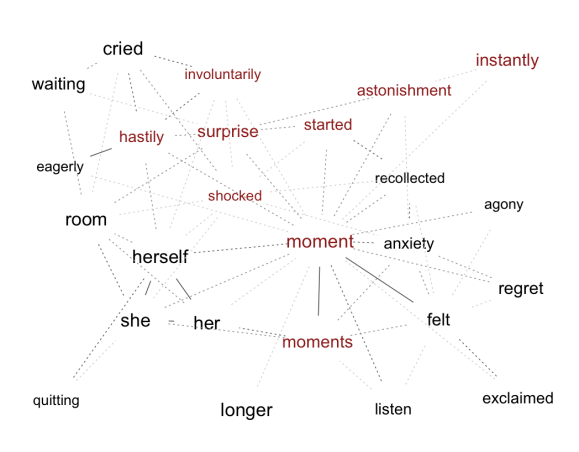

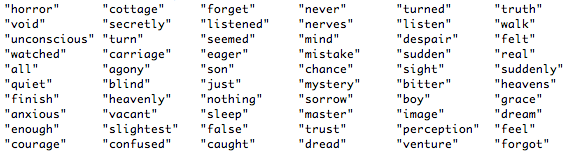

In other words, we want to find the words that became overrepresented in fiction as fiction was becoming less like nonfiction prose. To find them, I compared fiction to nonfiction at five-year intervals between 1720 and 1880. At each interval I selected a 39-year slice of the collection and ranked words according to the extent to which they were consistently more prominent in fiction than nonfiction (using Mann-Whitney rho). After moving through the whole timeline you end up with a curve for each word that plots the degree to which it is over or under-represented in fiction over time. Then you sort the words to find ones that tend to become more common in fiction as the whole genre becomes less like nonfiction. (Technically, you’re looking for an inverse Pearson’s correlation, over time, between the Mann-Whitney rho for this word and the Spearman’s similarity between genres.) Here’s a list of the top 60 words you find when you do that:

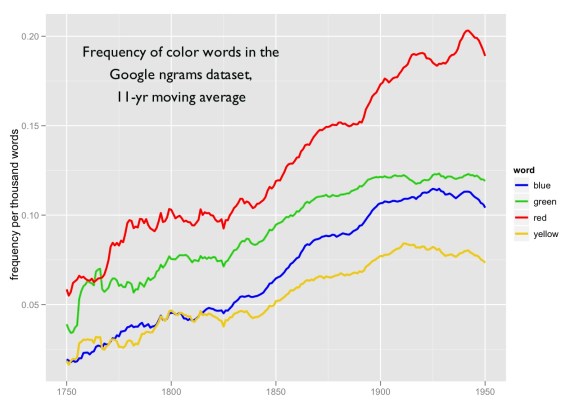

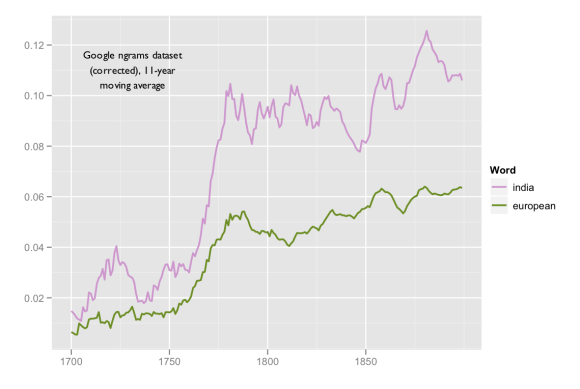

It’s not hard to see that there are a lot of words for emotional conflict here (“horror, courage, confused, eager, anxious, despair, sorrow, dread, agony”). But I would say that emotion is just one aspect of a more general emphasis on subjectivity, ranging from verbs of perception (“listen, listened, watched, seemed, feel, felt”) to explicitly psychological vocabulary (“nerves, mind, unconscious, image, perception”) to questions about the accuracy of perception (“dream, real, sight, blind, forget, forgot, mystery, mistake”). To be sure, there are other kinds of words in the list (“cottage, boy, carriage”). But since we’re looking at a change across a period of 200 years, I’m actually rather stunned by the thematic coherence of the list. For good measure, here are words that became relatively less common in fiction (or more common in nonfiction — that’s the meaning of “relatively”) as the two genres differentiated:

Looking at that list, I’m willing to venture out on a limb and suggest that fiction was specializing in subjectivity while nonfiction was tending to view the world from an increasingly social perspective (“executive, population, colonists, department, european, colonists, settlers, number, individuals, average.”)

Now, I don’t pretend to have solved this whole problem. First of all, the lists I just presented are based on fiction; I haven’t yet assessed whether there’s really a shared “literary diction” that unites fiction with poetry and drama. Jordan and I probably need to build up our collection a bit before we’ll know. Also, the technique I just used to select lists of words looks for correlations across the whole period 1700-1900, so it’s going to select words that have a relatively continuous pattern of change throughout this period. But it’s also entirely possible that “the differentiation of literary and nonliterary diction” was a phenomenon composed of several different, overlapping changes with a smaller “wavelength” on the time axis. So I would say that there’s lots of room here for alternate/additional explanations.

But really, this is a question that does need explanation. Literary scholars may hate the idea of “counting words,” but arguments about a distinctively “literary” language have been central to literary criticism from John Dryden to the Russian Formalists. If we can historicize that phenomenon — if we can show that a systematic distinction between literary and nonliterary language emerged at a particular moment for particular reasons — it’s a result that ought to have significance even for literary scholars who don’t consider themselves digital humanists.

By the way, I think I do know why the results I’m presenting here don’t line up with our received impression that “poetic diction” is an eighteenth-century phenomenon that fades in the 19c. There is a two-part answer. For one thing, part of what we perceive as poetic diction in the 18c is orthography (“o’er”, “silv’ry”). In this collection, I have deliberately normalized orthography, so “silv’ry” is treated as equivalent to “silvery,” and that aspect of “poetic diction” is factored out.

But we may also miss differentiation because we wrongly assume that plain or vivid language cannot be itself a form of specialization. Poetic diction probably did become more accessible in the 19c than it had been in the 18c. But this isn’t the same thing as saying that it became less specialized! A self-consciously plain or restricted diction still counts as a mode of specialization relative to other written genres. More on this in a week or two …

Finally, let me acknowledge that the work I’m doing here is built on a collaborative foundation. Laura Mandell helped me obtain the TCP-ECCO volumes before they were public, and Jordan Sellers selected most of the nineteenth-century collection on which this work is based — something over 1,600 volumes. While Jordan and I were building this collection, we were also in conversation with Loretta Auvil, Boris Capitanu, Tanya Clement, Ryan Heuser, Matt Jockers, Long Le-Khac, Ben Schmidt, and John Unsworth, and were learning from them how to do this whole “text mining” thing. The R/MySQL infrastructure for this is pretty directly modeled on Ben’s. Also, since the work was built on a collaborative foundation, I’m going to try to give back by sharing links to my data and code on this “Open Data” page.

References

Adam Kilgarriff, “Comparing Corpora,” International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 6.1 (2001): 97-133.

[UPDATE Monday Feb 27th, 7 pm: After reading Ben Schmidt’s comment below, I realized that I really had to normalize corpus size. “Probably not a problem” wasn’t going to cut it. So I wrote a script that samples a million-word corpus for each genre every two years. As long as I was addressing that problem, I figured I would address another one that had been nagging at my conscience. I really ought to be comparing a different wordlist each time I run the comparison. It ought to be the top 5000 words in each pair of corpora that get compared — not the top 5000 words in the collection as a whole.

The first time I ran the improved version I got a cloud of meaningless dots, and for a moment I thought my whole hypothesis about genre had been produced by a ‘loose optical cable.’ Not a good moment. But it was a simple error, and once I fixed it I got results that were actually much clearer than my earlier graphs.

I suppose you could argue that, since document size varies across time, it’s better to select corpora that have a fixed number of documents rather than a fixed word size. I ran the script that way too, and it produces results that are noisier but still unambiguous. The moral of the story is: it’s good to have blog readers who keep you honest and force you to clean up your methodology!]