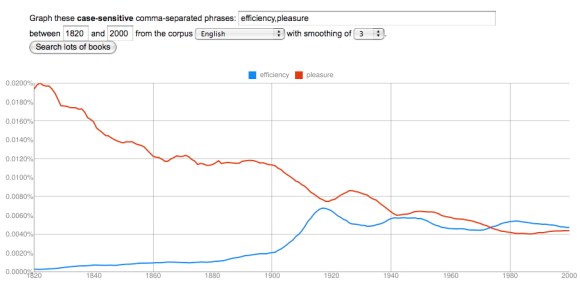

It’s tempting to use the ngram viewer to stage semantic contrasts (efficiency vs. pleasure). It can be more useful to explore cases of semantic replacement (liberty vs. freedom). But a third category of comparison, perhaps even more interesting, involves groups of words that parallel each other quite closely as the whole group increases or decreases in prominence.

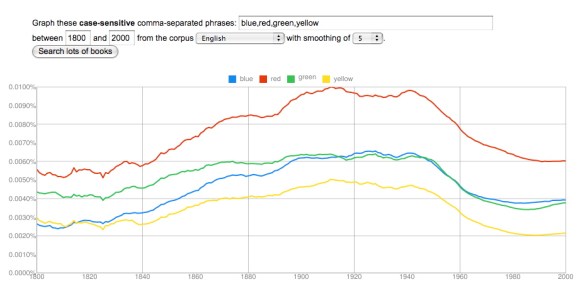

One example that is conveniently easy to visualize involves colors.

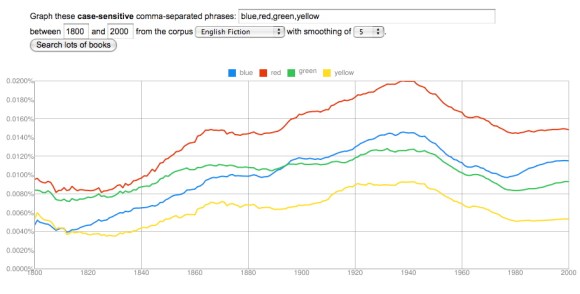

The trajectories of primary colors parallel each other very closely. They increase in frequency through the nineteenth century, peak in a period between 1900 and 1945, and then decline to a low around 1985, with some signs of recovery. (The recovery is more marked after 2000, but that data may not be reliable yet.) Blue increases most, by a factor of almost three, and green the least, by about 50%. Red and yellow roughly double in frequency.

Perhaps red increases because of red-baiting, and blue increases because jazz singers start to use it metaphorically? Perhaps. But the big picture here is that the relative prominence of different colors remains fairly stable (red being always most prominent), while they increase and decline significantly as a group. This is a bit surprising. Color seems like a basic dimension of human experience, and you wouldn’t expect its importance to fluctuate. (If you graph the numbers one, two, three, for instance, you get fairly flat lines all the way across.)

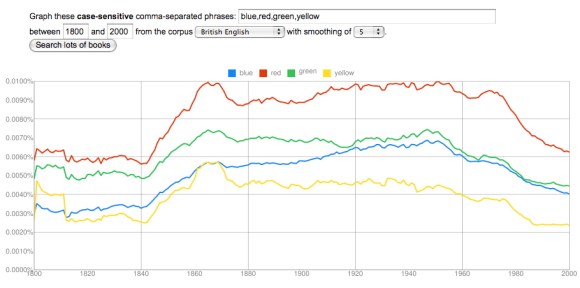

What about technological change? Color photography is really too late to be useful. Maybe synthetic dyes? They start to arrive on the scene in the 1860s, which is also a little late, since the curves really head up around 1840, but it’s conceivable that a consumer culture with a broader range of artefacts brightly differentiated by color might play a role here. If you graph British usage, there’s even an initial peak in the 1860s and 70s that looks plausibly related to the advent of synthetic dye.

On the other hand, if this is a technological change, it’s a little surprising that it looks so different in different national traditions. (The French and German corpora may not be reliable yet, but at this point their colors behave altogether differently.) Moreover, a hypothesis about synthetic dyes wouldn’t do much to explain the equally significant decline from the 1950s to the 1980s. Maybe the problem is that we’re only looking at primary colors. Perhaps in the twentieth century a broader range of words for secondary colors proliferated, and subtracted from the frequency of words like red and green?

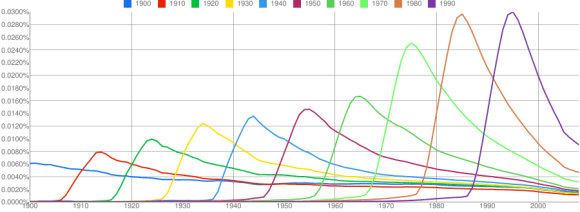

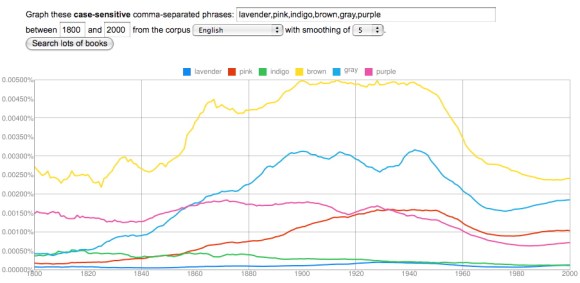

This is a hard hypothesis to test, because there are a lot of different words for color, and you’d need to explore perhaps a hundred before you had a firm answer. But at first glance, it doesn’t seem very helpful, because a lot of words for minor colors exhibit a pattern that closely resembles primary colors. Brown, gray, purple, and pink — the leaders in the graph above — all decline from 1950 to 1980. Even black and white (not graphed here) don’t help very much; they display a similar pattern of increase beginning around 1840 and decrease beginning around 1940, until the 1960s, when the racial meanings of the terms begin to clearly dominate other kinds of variation.

At the moment, I think we’re simply looking at a broad transformation of descriptive style that involves a growing insistence on concrete and vivid sensory detail. One word for this insistence might be “realism.” We ordinarily apply that word to fiction, of course, and it’s worth noting that the increase in color vocabulary does seem to begin slightly earlier in the corpus of fiction — as early perhaps as the 1820s.

But “realism,” “naturalism,” “imagism,” and so on are probably not adequate words for a transformation of diction that covers many different genres and proceeds for more than a century. (It proceeds fairly steadily, although I would really like to understand that plateau from 1860 to 1890.) More work needs to be done to understand this. But the example of color vocabulary already hints, I think, that broadly diachronic studies of diction may turn up literary phenomena that don’t fit easily into literary scholars’ existing grid of periods and genres. We may need to define a few new concepts.