Right now, humanists often have to take topic modeling on faith. There are several good posts out there that introduce the principle of the thing (by Matt Jockers, for instance, and Scott Weingart). But it’s a long step up from those posts to the computer-science articles that explain “Latent Dirichlet Allocation” mathematically. My goal in this post is to provide a bridge between those two levels of difficulty.

Computer scientists make LDA seem complicated because they care about proving that their algorithms work. And the proof is indeed brain-squashingly hard. But the practice of topic modeling makes good sense on its own, without proof, and does not require you to spend even a second thinking about “Dirichlet distributions.” When the math is approached in a practical way, I think humanists will find it easy, intuitive, and empowering. This post focuses on LDA as shorthand for a broader family of “probabilistic” techniques. I’m going to ask how they work, what they’re for, and what their limits are.

How does it work? Say we’ve got a collection of documents, and we want to identify underlying “topics” that organize the collection. Assume that each document contains a mixture of different topics. Let’s also assume that a “topic” can be understood as a collection of words that have different probabilities of appearance in passages discussing the topic. One topic might contain many occurrences of “organize,” “committee,” “direct,” and “lead.” Another might contain a lot of “mercury” and “arsenic,” with a few occurrences of “lead.” (Most of the occurrences of “lead” in this second topic, incidentally, are nouns instead of verbs; part of the value of LDA will be that it implicitly sorts out the different contexts/meanings of a written symbol.)

Of course, we can’t directly observe topics; in reality all we have are documents. Topic modeling is a way of extrapolating backward from a collection of documents to infer the discourses (“topics”) that could have generated them. (The notion that documents are produced by discourses rather than authors is alien to common sense, but not alien to literary theory.) Unfortunately, there is no way to infer the topics exactly: there are too many unknowns. But pretend for a moment that we had the problem mostly solved. Suppose we knew which topic produced every word in the collection, except for this one word in document D. The word happens to be “lead,” which we’ll call word type W. How are we going to decide whether this occurrence of W belongs to topic Z?

We can’t know for sure. But one way to guess is to consider two questions. A) How often does “lead” appear in topic Z elsewhere? If “lead” often occurs in discussions of Z, then this instance of “lead” might belong to Z as well. But a word can be common in more than one topic. And we don’t want to assign “lead” to a topic about leadership if this document is mostly about heavy metal contamination. So we also need to consider B) How common is topic Z in the rest of this document?

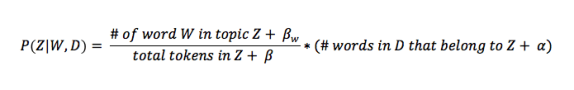

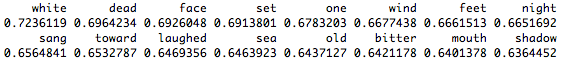

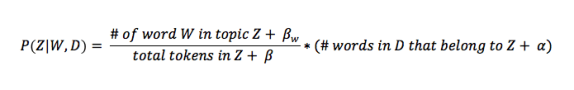

Here’s what we’ll do. For each possible topic Z, we’ll multiply the frequency of this word type W in Z by the number of other words in document D that already belong to Z. The result will represent the probability that this word came from Z. Here’s the actual formula:

Simple enough. Okay, yes, there are a few Greek letters scattered in there, but they aren’t terribly important. They’re called “hyperparameters” — stop right there! I see you reaching to close that browser tab! — but you can also think of them simply as fudge factors. There’s some chance that this word belongs to topic Z even if it is nowhere else associated with Z; the fudge factors keep that possibility open. The overall emphasis on probability in this technique, of course, is why it’s called probabilistic topic modeling.

Now, suppose that instead of having the problem mostly solved, we had only a wild guess which word belonged to which topic. We could still use the strategy outlined above to improve our guess, by making it more internally consistent. We could go through the collection, word by word, and reassign each word to a topic, guided by the formula above. As we do that, a) words will gradually become more common in topics where they are already common. And also, b) topics will become more common in documents where they are already common. Thus our model will gradually become more consistent as topics focus on specific words and documents. But it can’t ever become perfectly consistent, because words and documents don’t line up in one-to-one fashion. So the tendency for topics to concentrate on particular words and documents will eventually be limited by the actual, messy distribution of words across documents.

That’s how topic modeling works in practice. You assign words to topics randomly and then just keep improving the model, to make your guess more internally consistent, until the model reaches an equilibrium that is as consistent as the collection allows.

What is it for? Topic modeling gives us a way to infer the latent structure behind a collection of documents. In principle, it could work at any scale, but I tend to think human beings are already pretty good at inferring the latent structure in (say) a single writer’s oeuvre. I suspect this technique becomes more useful as we move toward a scale that is too large to fit into human memory.

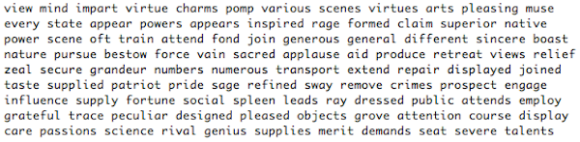

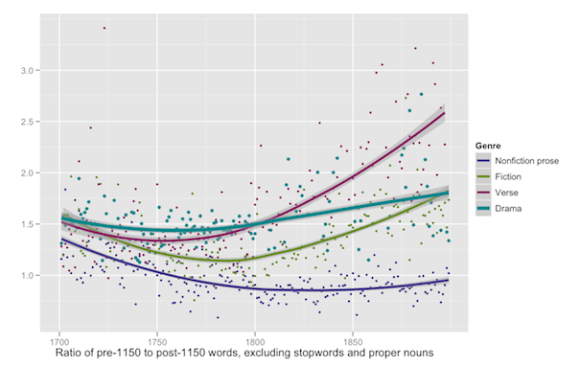

So far, most of the humanists who have explored topic modeling have been historians, and I suspect that historians and literary scholars will use this technique differently. Generally, historians have tried to assign a single label to each topic. So in mining the Richmond Daily Dispatch, Robert K. Nelson looks at a topic with words like “hundred,” “cotton,” “year,” “dollars,” and “money,” and identifies it as TRADE — plausibly enough. Then he can graph the frequency of the topic as it varies over the print run of the newspaper.

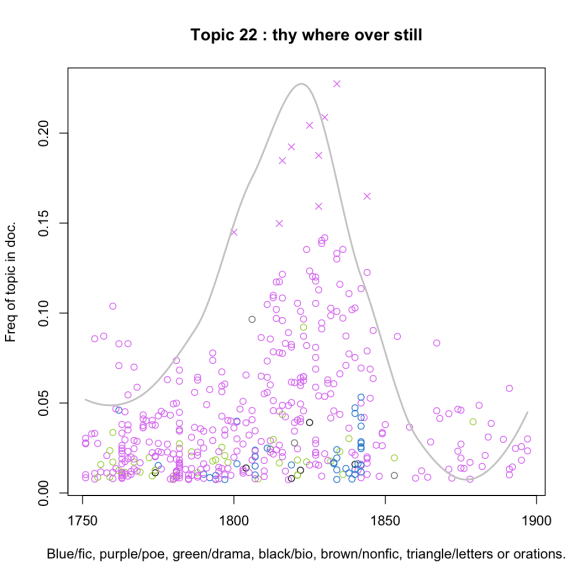

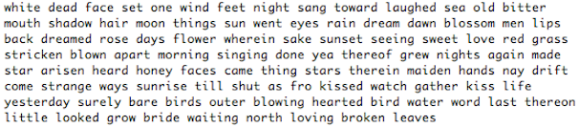

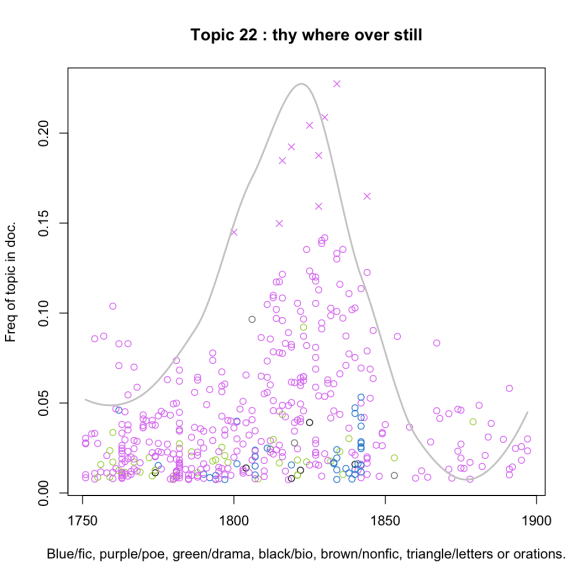

As a literary scholar, I find that I learn more from ambiguous topics than I do from straightforwardly semantic ones. When I run into a topic like “sea,” “ship,” “boat,” “shore,” “vessel,” “water,” I shrug. Yes, some books discuss sea travel more than others do. But I’m more interested in topics like this:

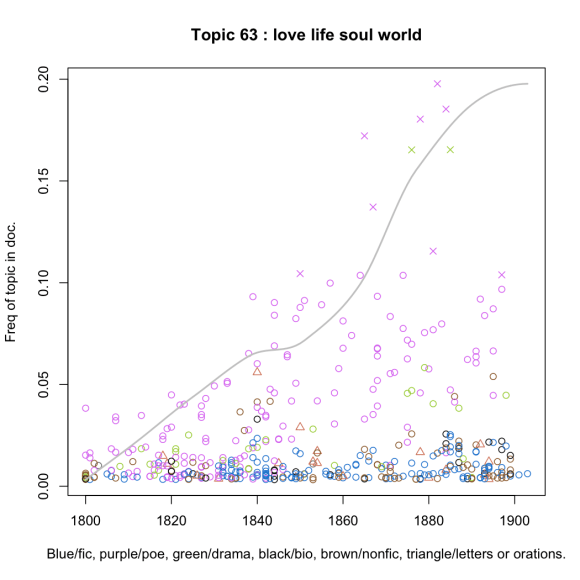

You can tell by looking at the list of words that this is poetry, and plotting the volumes where the topic is prominent confirms the guess.

This topic is prominent in volumes of poetry from 1815 to 1835, especially in poetry by women, including Felicia Hemans, Letitia Landon, and Caroline Norton. Lord Byron is also well represented. It’s not really a “topic,” of course, because these words aren’t linked by a single referent. Rather it’s a discourse or a kind of poetic rhetoric. In part it seems predictably Romantic (“deep bright wild eye”), but less colorful function words like “where” and “when” may reveal just as much about the rhetoric that binds this topic together.

A topic like this one is hard to interpret. But for a literary scholar, that’s a plus. I want this technique to point me toward something I don’t yet understand, and I almost never find that the results are too ambiguous to be useful. The problematic topics are the intuitive ones — the ones that are clearly about war, or seafaring, or trade. I can’t do much with those.

Now, I have to admit that there’s a bit of fine-tuning required up front, before I start getting “meaningfully ambiguous” results. In particular, a standard list of stopwords is rarely adequate. For instance, in topic-modeling fiction I find it useful to get rid of at least the most common personal pronouns, because otherwise the difference between 1st and 3rd person point-of-view becomes a dominant signal that crowds out other interesting phenomena. Personal names also need to be weeded out; otherwise you discover strong, boring connections between every book with a character named “Richard.” This sort of thing is very much a critical judgment call; it’s not a science.

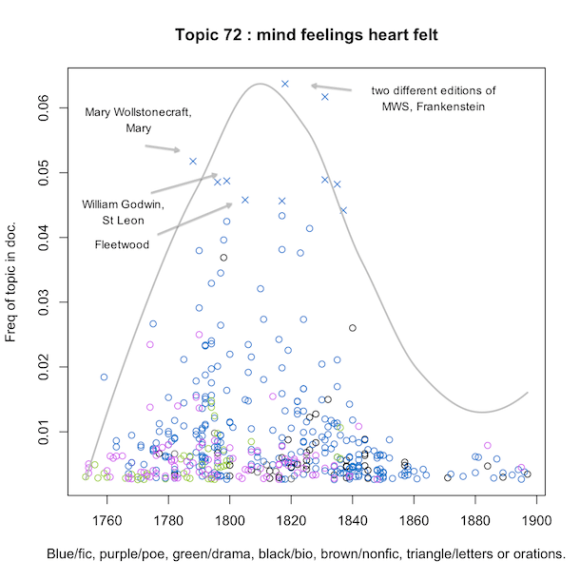

I should also admit that, when you’re modeling fiction, the “author” signal can be very strong. I frequently discover topics that are dominated by a single author, and clearly reflect her unique idiom. This could be a feature or a bug, depending on your interests; I tend to view it as a bug, but I find that the author signal does diffuse more or less automatically as the collection expands.

What are the limits of probabilistic topic modeling? I spent a long time resisting the allure of LDA, because it seemed like a fragile and unnecessarily complicated technique. But I have convinced myself that it’s both effective and less complex than I thought. (Matt Jockers, Travis Brown, Neil Fraistat, and Scott Weingart also deserve credit for convincing me to try it.)

This isn’t to say that we need to use probabilistic techniques for everything we do. LDA and its relatives are valuable exploratory methods, but I’m not sure how much value they will have as evidence. For one thing, they require you to make a series of judgment calls that deeply shape the results you get (from choosing stopwords, to the number of topics produced, to the scope of the collection). The resulting model ends up being tailored in difficult-to-explain ways by a researcher’s preferences. Simpler techniques, like corpus comparison, can answer a question more transparently and persuasively, if the question is already well-formed. (In this sense, I think Ben Schmidt is right to feel that topic modeling wouldn’t be particularly useful for the kinds of comparative questions he likes to pose.)

Moreover, probabilistic techniques have an unholy thirst for memory and processing time. You have to create several different variables for every single word in the corpus. The models I’ve been running, with roughly 2,000 volumes, are getting near the edge of what can be done on an average desktop machine, and commonly take a day. To go any further with this, I’m going to have to beg for computing time. That’s not a problem for me here at Urbana-Champaign (you may recall that we invented HAL), but it will become a problem for humanists at other kinds of institutions.

Probabilistic methods are also less robust than, say, vector-space methods. When I started running LDA, I immediately discovered noise in my collection that had not previously been a problem. Running headers at the tops of pages, in particular, left traces: until I took out those headers, topics were suspiciously sensitive to the titles of volumes. But LDA is sensitive to noise, after all, because it is sensitive to everything else! On the whole, if you’re just fishing for interesting patterns in a large collection of documents, I think probabilistic techniques are the way to go.

Where to go next

The standard implementation of LDA is the one in MALLET. I haven’t used it yet, because I wanted to build my own version, to make sure I understood everything clearly. But MALLET is better. If you want a few examples of complete topic models on collections of 18/19c volumes, I’ve put some models, with R scripts to load them, in my github folder.

If you want to understand the technique more deeply, the first thing to do is to read up on Bayesian statistics. In this post, I gloss over the Bayesian underpinnings of LDA because I think the implementation (using a strategy called Gibbs sampling, which is actually what I described above!) is intuitive enough without them. And this might be all you need! I doubt most humanists will need to go further. But if you do want to tinker with the algorithm, you’ll need to understand Bayesian probability.

David Blei invented LDA, and writes well, so if you want to understand why this technique has “Dirichlet” in its name, his works are the next things to read. I recommend his Introduction to Probabilistic Topic Models. It recently came out in Communications of the ACM, but I think you get a more readable version by going to his publication page (link above) and clicking the pdf link at the top of the page.

Probably the next place to go is “Rethinking LDA: Why Priors Matter,” a really thoughtful article by Hanna Wallach, David Mimno, and Andrew McCallum that explains the “hyperparameters” I glossed over in a more principled way.

Then there are a whole family of techniques related to LDA — Topics Over Time, Dynamic Topic Modeling, Hierarchical LDA, Pachinko Allocation — that one can explore rapidly enough by searching the web. In general, it’s a good idea to approach these skeptically. They all promise to do more than LDA does, but they also add additional assumptions to the model, and humanists are going to need to reflect carefully about which assumptions we actually want to make. I do think humanists will want to modify the LDA algorithm, but it’s probably something we’re going to have to do for ourselves; I’m not convinced that computer scientists understand our problems well enough to do this kind of fine-tuning.