Several times in the last year I’ve been surprised when students who I thought were still learning to program showed up to our meeting with a fully-formed (good) solution to a challenging research problem.

In part, this is just what it feels like to work with students. “Wait, I thought you couldn’t do that, and now you’re telling me you can do it? You somehow learned to do it?”

But there’s also a specific reason why students are surprising me more often lately. In each of these cases, when my eyes widened, the student minimized their own work by adding “oh, it’s easy with ChatGPT.”

I understand what they mean, because I’m having the same experience. As Simon Willison has put it, “AI-enhanced development makes me more ambitious with my projects.” The effect is especially intense if you code, because AI code completion is like wearing seven-league boots. But it’s not just for coding. Natural-language dialogue with a chatbot also helps me understand new concepts and choose between tools.

As in any fairytale, accepting magical assistance comes with risks. Chatbot advice has saved me several days on a project, but if you add up bugs and mistakes it has cost me at least a day too. And it’s hard to find bugs if you’re not the person who put them in! I won’t try to draw up a final balance sheet here, because a) as tools evolve, the balance will keep changing, and b) people have developed very strong priors on the topic of “AI hallucination” and I don’t expect to persuade readers to renounce them.

Instead, let’s agree to disagree about the ratio of “really helping” to “encouraging overconfidence.” What I want to say in this short post is just that, when it comes to education, even encouraging overconfidence can have positive effects. A lot of learning takes place when we find an accessible entry point to an actually daunting project.

I suspect this is how the internet encouraged so many of us to venture across disciplinary boundaries. I don’t have a study to prove it, but I guess I’ve lived it, because I considered switching disciplines twice in my career. The first attempt, in the 1990s, came to nothing because I started by going to the library and checking out an introductory textbook. Yikes: it had like five hundred pages. By 2010 things were different. Instead of starting with a textbook you could go straight to a problem you wanted to solve and Google around until you found a blog solving a related problem and — hmm — it says you have to download this program called “R,” but how hard can that be? just click here …

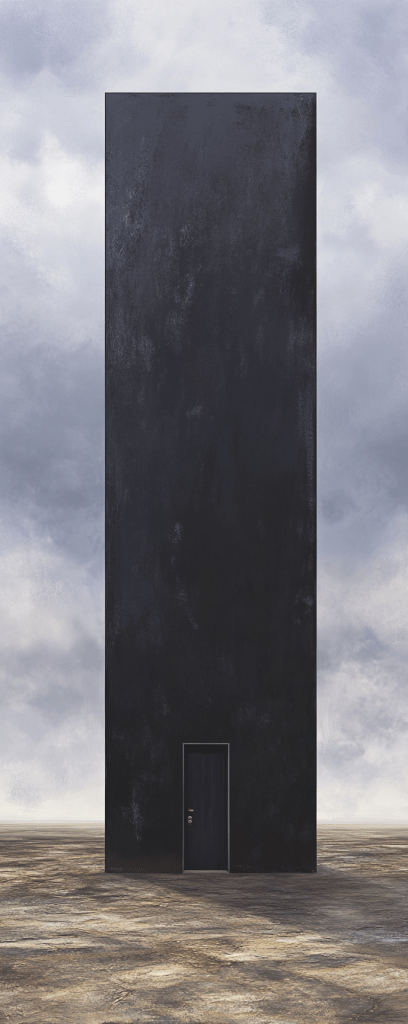

As in the story of “Stone Soup,” the ease was mostly deceptive. In fact I needed to back up and learn statistics in order to understand the numbers R was going to give me, and that took a few years more than I expected. But it’s still good for everyone that the interactive structure of the internet has created accessible entry points to difficult problems. Even if the problem is in fact still a daunting monolith … now it has a tempting front door.

In many ways, generative AI is just an extension of a project that the internet started thirty years ago: a project to reorganize knowledge interactively. Instead of starting by passively absorbing a textbook, we can can cobble together solutions from pieces we find in blogs and Stack Overflow threads and GitHub repos. Language models are extensions of this project, of course, in the literal sense that they were trained on Stack Overflow threads and GitHub repos! And I know people have a range of opinions about whether that training counts as fair use.

But let’s save the IP debate for another day. All I want to say right now is that the effects of generative AI are also likely to resemble the effects of the shift toward interactivity that began with the Web. In many cases, we’re not really getting a robot who can do a whole project for us. We’re getting an accessible front door, perhaps in the form of a HuggingFace page, plus a chatty guide who will accompany us inside the monolith and help us navigate the stairs. With this assistance, taking on unfamiliar tasks may feel less overwhelming. But the guide is fallible! So it’s still on us to understand our goal and recognize wrong turns.

Is the net effect of all this going to be good or bad? I doubt anyone knows. I certainly don’t. The point of this post is just to encourage us to reframe the problem a little. Our fears and fantasies about AI currently lean very heavily on a narrative frame where we “prompt it” to “do a task for us.” Sometimes we get angry—as with the notorious “Dear Sydney” ad—and insist that people still need to “do that for themselves.”

While that’s fair, I’d suggest flipping the script a little. Once we get past the silly-ad phase of adjusting to language models, the effect of this technology may actually be to encourage people to try doing more things for themselves. The risk is not necessarily that AI will make people passive; in fact, it could make some of us more ambitious. Encouraging ambition has upsides and downsides. But anyway, “automation” might not be exactly the right word for the process. I would lean instead toward stories about seven-league boots and animal sidekicks who provide unreliable advice.*

(* PS: For this reason, I think the narrator/sidekick in Robin Sloan’s Moonbound may provide a better parable about AI than most cyberpunk plots that hinge on sublime/terrifying/godlike singularities.)