Since Mary Shelley, writers of science fiction have enjoyed musing about the moral dilemmas created by artificial persons.

I haven’t, to be honest. I used to insist on the term “machine learning,” because I wanted to focus on what the technology actually does: model data. Questions about personhood and “alignment” felt like anthropocentric distractions, verging on woo.

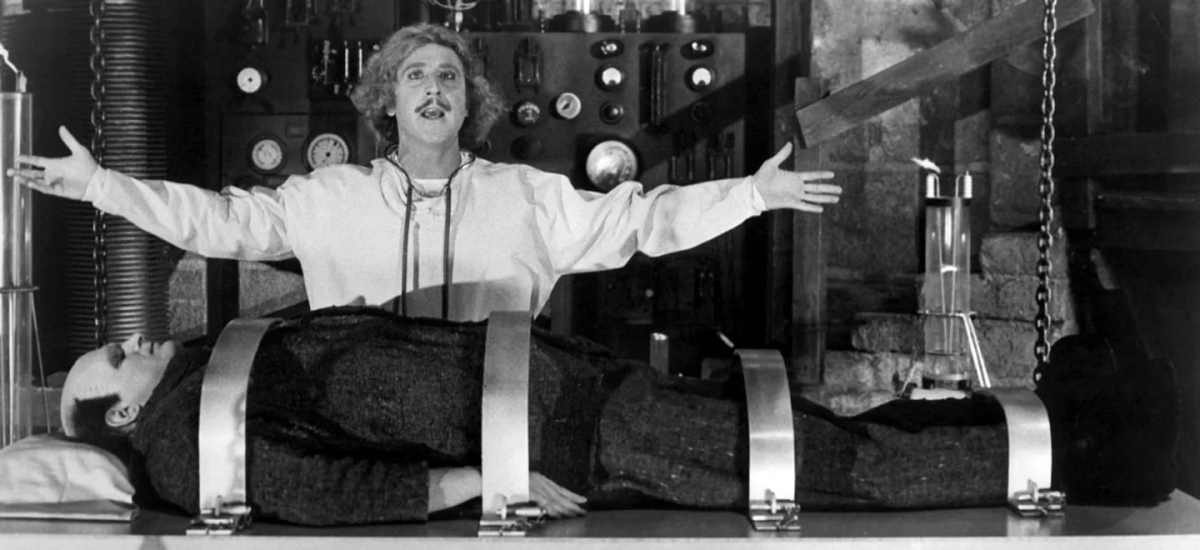

But these days woo is hard to avoid. OpenAI is now explicitly marketing the promise that AI will cross the uncanny valley and start to sound like a person. The whole point of the GPT-4o demo was to show off the human-sounding (and um, gendered) expressiveness of a new model’s voice. If there had been any doubt about the goal, Sam Altman’s one-word tweet “her” removed it.

At the other end of the spectrum lies Apple, which seems to be working hard to avoid any suggestion that the artificial intelligence in their products could coalesce into an entity. The phrase “Apple Intelligence” has a lot of advantages, but one of them is that it doesn’t take a determiner. It’s Apple Intelligence, not “an apple intelligence.” Apple’s conception of this feature is more like an operating system — diffuse and unobtrusive — just a transparent interface to the apps, schedules, and human conversations contained on your phone.

If OpenAI is obsessed with Her, Apple Intelligence looks more like a Caddy from All the Birds in the Sky. In Charlie Jane Anders’ novel, Caddies are mobile devices that quietly guide their users with reminders and suggestions (restaurants you might like, friends who happen to be nearby, and so on). A Caddy doesn’t need an expressive voice, because it’s a service rather than a separate person. In All the Birds, Patricia starts to feel it’s “an extension of her personality” (173).

There are a lot of reasons to prefer Apple’s approach. Putting the customer at the center of a sales pitch is usually a smart move. Ben Evans also argues that users will understand the limitations of AI better if it’s integrated into interfaces that provide a specific service rather than presented as an open-ended chatbot.

Moreover, Apple’s approach avoids several kinds of cringe invited by OpenAI’s demo — from the creepily-gendered Pygmalion vibe to the more general problem that we don’t know how to react to the laughter of a creature that doesn’t feel emotion. (Readers of Neuromancer may remember how much Case hates “the laugh that wasn’t laughter” emitted by the recording of his former teacher, the Dixie Flatline.)

Finally, impersonal AI is calculated to please grumpy abstract thinkers like me, who find a fixation on so-called “general” intelligence annoyingly anthropocentric.

However. Let’s look at the flip side for a second.

The most interesting case I’ve heard for person-shaped AI was offered last week by Amanda Askell, a philosopher working at Anthropic. In an interview with Stuart Richie, Askell argues that AI needs a personality for two reasons. First, shaping a personality is how we endow models with flexible principles that will “determine how [they] react to new and difficult situations.” Personality, in other words, is simply how we reason about character. Second, personality signals to users that they’re not talking to an omniscient oracle.

“We want people to know that they’re interacting with a language model and not a person. But we also want them to know they’re interacting with an imperfect entity with its own biases and with a disposition towards some opinions more than others. Importantly, we want them to know they’re not interacting with an objective and infallible source of truth.”

It’s a good argument. One has to approach it skeptically, because there are several other profitable reasons for companies to give their products a primate-shaped UI. It provides “a more interesting user experience,” as Askell admits — and possibly a site of parasocial attachment. (OpenAI’s Sky voice sounded a bit like Scarlett Johansson.) Plus, human behavior is just something we know how to interpret. I often prefer to interact with ChatGPT in voice mode, not only because it leaves my hands and eyes free, but because it gives the model an extra set of ways to direct my attention — ranging from emphasis to, uh, theatrical pauses that signal a new or difficult topic.

But this ends up sending us back to Askell’s argument. Even if models are not people, maybe we need the mask of personality to understand them? A human-sounding interface provides both simple auditory signals and epistemic signals of bias and limitation. Suppressing those signals is not necessarily more honest. It may be relevant here that the impersonal transparency of the Caddies in All the Birds in the Sky turns out to be a lie. No spoilers, but the Caddies actually have an agenda, and are using those neutral notifications and reminders to steer their human owners. It wouldn’t be shocking if corporate interfaces did the same thing.

So, should we anthropomorphize AI? I think it’s a much harder question than is commonly assumed, and maybe not a question that can be answered at all. Apple and Anthropic are selling different products, to different audiences. There’s no reason one of them has to be wrong.

More fundamentally, this is a hard question because it’s not clear that we’re telling the full truth when we anthropomorphize people. Writers and critics have been arguing for a long time that the personality of the author is a mask. As Stéphane Mallarmé puts it, “the pure work implies the disappearance of the poet speaking, who yields the initiative to words” (208). There’s a sense in which all of us are language models. “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?”

So if we feel creeped out by all the interfaces for artificial intelligence — both those that pretend to be neutrally helpful and those that pretend to laugh at our jokes — the reason may be that this dilemma reminds us of something slightly cringe and theatrical about personality itself. Our selves are not bedrock atomic realities; they’re shaped by collective culture, and the autonomy we like to project is mostly a fiction. But it’s also a necessary fiction. Projecting and perceiving personality is how we reason about questions of character and perspective, and we may end up trusting models more if they can play the same game. Even if we flinch a little every time they laugh.

References

Anders, Charlie Jane. All the Birds in the Sky. Tor, 2016.

Askell, Amanda and Richie, Stuart. “What should an AI’s personality be?” Anthropic blog. June 8, 2024.

Gibson, William. Neuromancer. Ace, 1984.

Mallarmé, Stéphane. “The Crisis of Verse.” In Divagations, trans Barbara Johnson. Harvard University Press, 2007.

Warner Bros. Picture presents an Annapurna Pictures production; produced by Megan Ellison, Spike Jonze, Vincent Landay; written and directed by Spike Jonze. Her. Burbank, CA: Distributed by Warner Home Video, 2014.

2 replies on “Should artificial intelligence be person-shaped?”

[…] 详情参考 […]

brilliant stuff, as ever – thank you!!